|

Home Page

Discovery of Atlantis

First Empire-(1) to 261

Second Empire- (1) 361 - 409 |

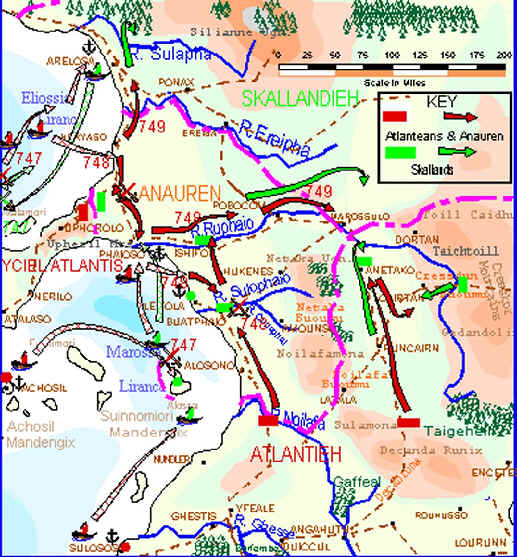

Success for Atlantis in the north; in the south, the Basquecs hold the line, 748 THE SLOWING DOWN OF THE WAR AGAINST THE BASQUECS After the great successes of 747, it appeared to both sides in the War that the victory of Atlantis and her allies must take place within the next year. However, this view soon seemed cruelly mistaken. Certainly, Atlantean advances continued in the north, where she undertook a meticulously prepared and wholly successful amphibious invasion of Anauren, while Gestskallandieh continued to make inroads into Skalland territory. But these successes did not end the war with Skallandieh, and later in the year, Atlantean and Gestskalland armies had bogged down again. The war against the Ughans was less successful, and despite the Atlantean and Gestskalland armies gradually forcing them back into the Ughan interior, the war was still going on at the end of the year. As far as the Basquecs were concerned, Gosscalt showed his strategic genius at its greatest, moving quickly between the Atlantean and Rabarran armies, and defeating or halting each in turn. The allies were not helped by the increasing mistrust between Atlanteans and Basquecs over their war plans and objectives, after the final defeat of the Basquecs. The Rabarrans, although still the recipients of large amounts of military aid from the Atlanteans, resented being tied to their war aims, which obviously involved the restoration of the former Atlantean Empire, at the expense of both Basquecieh and Rabarrieh. The Rabarrans wanted to make their own way to victory, and conclude their own peace-terms with the Basquecs, irrespective of the aspirations of their overbearing ally. Atlantis, of course, wanted to make sure she reaped the benefits and glory of the defeat of the Basquecs, but found, as the year progressed, that for reasons of both geographical distance and internal military and political difficulties, she could not match the growing strength of the Rabarran armies. Thus it was a simple geographical fact that the Rabarran armies, especially after they had split from any united command with the Atlanteans, were much closer to the heart of the Basquec Empire than was their ally: the Atlantean forces were hundreds of miles from Bavcuat or Quachach, whether in Manralia or on the river Gestes. Moreover, although the overall Atlantean armed forces reached a peak of some 1400000 men at the start of 748, their numbers fell off rapidly after that. By the beginning of 749, they were down to 855000 and falling (especially those actually at the frontline), while the Rabarrans had gone up from 700000 in 748 to 790000 by 749, and passed the Atlantean total later in that year. There are various reasons for this Atlantean decline. One was that Brancerix was finding it increasingly difficult to conscript more men, due to organisational shortcomings, war casualties, lack of manpower available, and outright opposition to the continuing war. Thus, while the enemies of Atlantis were threatening her very heart, the citizens of the Empire were very willing to fight to defend her. But by 748 and 749, when all or nearly all Atlantean territory was cleared of enemy forces, many people felt a much diminished urge to risk their lives in the war. Furthermore, as we shall see in more detail below, political opposition to the Third Empire regime was building up fast. This meant more unwillingness to fight for a hated Government, and the need to deploy more and more forces internally to quell riots and other armed opposition. GOSSCALT’S PLAN TO SAVE HIS COUNTRY Gosscalt had spent the winter reconstituting his main army on the Gestes at Vulcanipand, and creating a mobile strategic force of 80000 men. At the same time, he made his first – and only – feelers for peace with Atlantis. But his conditions were utterly unacceptable, demanding that the Basquecs should retain all the territory still in their hands south of the river Gestes, and east of the Gairase. He refused to treat with the Rabarrans, and obviously intended to throw his whole army against that nation, if he obtained peace from the Atlanteans. Anyway the negotiations came to nothing. Gosscalt now intended to use a central strategic force plus himself to reinforce the army on the Itheerdi, and crush the Rabarrans there, then move to relieve Atlaniphis, and finally return to deal with the main Atlantean army, still west of the Gestes, as he hoped. If he was successful, he could then either carry on with proper offensives, or try again to make Atlantis settle for peace. Elsewhere, he would stay on the defensive. So during March, he reinforced his army on the Itheerdi, near the Basquec border to 170000 men, and hurled it at the Rabarrans, who had 180000 men, many of them straggled out in little groups along the river. In the Battles of the River Itheerdi on April 2nd-7th, Gosscalt crushed parts of these forces in detail, and sent them all retreating many miles eastwards up the river. He then turned his mobile force northwards to Atlaniphis. Here he joined the army of 60000 men already in place, facing about 65000 Atlanteans. An initial attack forced the Atlanteans back, and Gosscalt surrounded the city, and began its siege at the beginning of May. Atlantean attempts to relieve it repeatedly failed, and Buentel was forced to abandon his siege of Noutens, and bring 30000 more men south to try to force the Basquecs back. Gosscalt had foreseen this, and his forces in Noutens emerged and harassed the rear of the retreating Atlanteans. But then a new emergency arose. Gosscalt had always intended to finally move on north, and fight the Atlanteans west of the Gestes, but at the beginning of June, he received news that this army, having earlier made some ineffectual gestures against the Basquec forces in the well-defended Vulcanipand position, had seized Borepande, and crossed the river. In fact Lingon had soon become aware that he could not defeat the well-defended enemy force at Vulcanipand (although it was only half the strength of his army), and his lunges here were only ruses. At the end of May, he suddenly threw 110000 men against the much less well-defended fortress of Borepande. The Basquecs here, numbering only 40000, defended well, but were out manoeuvred and surrounded in the fort. Leaving a besieging force behind, Lingon now crossed the Gestes with 90000 men. He advanced south down the east of the river, and crossed the Thawril. The Basquec Vulcanipand army succeeded in limiting any further move south by the Atlanteans, and held them back till the hurried arrival of Gosscalt and his mobile force at the end of June. There followed a series of cautious manoeuvres by the two sides. Gosscalt deliberately drew Atlanteans south, over the river Vulcan, while maintaining a strong force in Vulcanipand. Then, on July 20th, he struck. He counter-attacked across the Thawril with 80000 men, and a force of 40000 emerged from Vulcanipand against the enemy flank. This Battle of the River Vulcan saw the Atlanteans badly defeated, losing 30000 men out of 100000, and forced to retreat northward. But they still remained on the east of the Gestes, and ultimately the Basquecs were unable to force them back across it. Few further successes were obtained by Atlanteans or Rabarrans elsewhere, either. Buentel did relieve the siege of Atlaniphis eventually, at the cost of having abandoned the siege of Noutens. On the other hand, the city of Dohgash, the only other one still in Basquec hands in Manralia, fell to the Atlanteans on their march south from Noutens. The siege of Noutens was re-established in the autumn, using reinforcements, and the city finally fell in December. To the south, Rabarran attacks against the Basquecs in the interior of the country, and on the river Basquec, were largely unsuccessful, especially when Gosscalt returned to take charge of this front after the Battle of the River Vulcan. The war with the Ughans produced few victories for the Atlanteans during this year. The Gestes was crossed in a few places, but the defensive positions of the Ughans in the Gestix Mountains were far too strong for the Atlanteans to be able to take them. Their army here had in any case been reduced to 90000 by the summer. Some more success was obtained by the Gestskallands, who were able to concentrate over 240000 men against 140000 Ughans in the north .By the end of 748, the Gestskallands had forced their way through the gap between the Gestix and Yrullia Mountains, and captured Yrullia in December. However, they were unable to reach the capital, Gargros, itself. THE AMPHIBIOUS INVASION OF SKALLANDIEH The main success for the Atlanteans in 748 was the amphibious invasion of Skallandieh. Having decided it was impossible to force a decision by land, a large armada, along with 40000 troops, was prepared, in order to invade Skallandieh by sea. As the Bay of Marossan was now under complete Atlantean control (the Skalland fleets were blockaded in Phaioso, and isolated in the Bay of Eliossia), the plan was to invade the former territory of Marossan jn the region south of the river Ruphaio.

The victory of Atlantis over Skallandieh, 747 - 749 The invasion duly took place on April 28th, and went off without hitch, the remains of the Skalland navy being blockaded in Phaioso. The invading troops turned south-eastwards after the landing, aiming to strike the Skalland forces defending the line of the river Noilafa in rear. The Skallands put up a strong resistance, and brought reinforcements north from the south. Nevertheless, they were decisively beaten at the Battle of Buatphaio, on May 22nd, and soon after, the Atlantean forces south of the Noilafa were able to advance northwards, and join up with the amphibious troops. However, the Atlanteans found themselves unable to gain any more successes in this area, as the Skallands poured in reinforcements. Now the area north of the river Ruphaio remained wholly in Skalland hands, and a perpetual threat to the left flank of the Atlanteans. So a second amphibious invasion was organised for later in the year, this time to the north, in the Bay of Eliossie, near Neryaso. A large naval force moved into the Bay in August, forcing the remains of the Skalland navy here back into port. Then the amphibious troops landed, as planned, on August 30th. Even greater surprise was achieved than in the earlier invasion, and soon the Atlanteans, numbering from 35000 to 50000 men, swept south, taking the Skalland troops on the border of Yciel Atlantis in rear. They then seized Phaioso, linked up with the southern forces, and moved 100 miles to the east, before the Skallands forced them to halt. By the end of the year, virtually the whole of former Anauren had been liberated, and the Skallands were defending their own Empire.

Atlantis: Victory abroad, civil turmoil at home, 749 GROWING DISCONTENT WITHIN THE EMPIRE In 749, Atlantis and her allies approached complete victory at last. In June, Ughrieh, her capital taken by the Gestskallands, sued for peace. Then in September, Skallandieh too, invaded by Atlantis and Gestskallandieh, surrendered. Only Basquecieh remained defiant by the end of the year, and she too was under siege by Atlantis and Rabarrieh, and could not survive much longer. And yet, despite these harbingers of victory, the Atlantean Empire became immersed in civil turmoil, and almost revolution, in 749. This disorder continued into 750, when final victory was gained over Basquecieh, and only finally ceased in 751, with the establishment of the Fourth Empire, and an entirely new social and political order. As we have already noted, discontent with the war had been growing for a year or more amongst Atlanteans unwilling to submit to conscription. Core Atlantean territory had already been largely cleared of the enemy, and victory seemed only a matter of time, so why should ordinary Atlanteans risk their lives unnecessarily? But this was only part of much wider social and political unrest. There was a growing impatience with the whole rigid Third Empire structure. Brancerix and the ruling Squires were determined not to change one iota of the social set-up, during or after the war. Yet the war itself was producing many changes of its own. Conscription and the movement of large armies all over the Empire and beyond led to increased social mobility, and a widening of the horizons of ordinary people. Large-scale industrialisation enhanced the importance of industrialists, factory-owners, and the middle classes in general. All these now wanted some participation in the running of the Empire. Equally, early military disasters and political mishaps had shown the need to extend participation in government and army beyond the elite, which currently ran the country. Indeed Brancerix had been forced to throw open careers in the military to the middle classes, and offer important posts to talented people, whatever their social class. He also created an Advisory Council of representatives from the major industrial towns in 746, and, on a limited scale, he included some "outsiders" in the governing circles. Finally, there had been cautious demands for political change for the past twenty years - more freedom, democracy, and social mobility -, but now, in the war years, these became much louder and more insistent. Up until 747, the government faced little trouble, as the whole population was concerned only to fight off the Empire’s enemies. But in 748 and 749, internal order in the Empire began to break down with frightening rapidity. Vocal demands for more of the population to be able to share in national and local government increased. Then, when occupying Basquec or Ughan troops were thrown out of lands and estates they had occupied in Dravidieh and Cennatlantis by the military counter-attacks of 747-8, the original landlords, usually Squires, found themselves unable to simply reoccupy their traditional places. They were threatened, evicted or removed from power by local people. The Government had to employ the Army to protect its representatives, and indeed Class 1 and 2 Squires, and several Provinces were placed under martial law in 748-9. However, this policy began to collapse, too, as unrest grew within the army itself, with revolts and disorder by lower ranks in favour of the non-landowning classes. Brancerix and his colleagues tried to crack down hard. The Emperor refused to make any further concessions after 748, and tried to turn the political clock back to 742. He aimed to keep the Army in Squire hands. He supported his Minister for the Provinces, who was leading the way by imprisoning objectors and dissidents, and enforcing martial law. He recreated the old Internal Security Force, now called the Internal Military Police. Most damningly, though, he made no attempt to alleviate the personal and economic hardship and suffering, which the war was producing in towns and countryside. This misery led to further disorder and food riots in many places throughout 749. Nevertheless, the Emperor tried desperately to unite the Empire, by asking them to make one last effort together to finish off the enemy, who were already so nearly beaten. "Tehens puancaxa ditontehe bourun cencsun ergain dan, puouthun e ruthouson, e losso ergain tontix ei teh e peth ulle malcethen". " We have nearly won the great battle for God, peace and happiness, and the freedom for all to do and think as they wish." THE OVERTHROW OF BRANCERIX III By 749, many in the ruling class had come to the decision that Brancerix himself would have to be sacrificed. Some felt a few concessions to the rebels would have to be made; others considered the Emperor had not been harsh enough in repressing the discontent. As a result, a successful and bloodless military coup took place in May, and Brancerix was removed from power. There were a few pre-emptive arrests of his closest supporters, but it is amazing how few friends he seemed to have, when the crunch came. He was allowed to retire to his estates, and his place was temporarily taken by an Imperial Succession Council, under the close control of the Army Generalissimo and three Officers of State. But the political crisis convulsing the Empire now went from bad to worse. The members of the new Council were totally unable to agree on anything themselves, and riots and disorder spread throughout the Empire. The parties now jockeying, and, increasingly, fighting for power, can be put into three groups. Firstly, the old Squirearchy - the landowning Classes 1 and 2 -, who were themselves divided into liberals, who were willing to make some further concessions, and traditionalists, who wanted to force the Empire back to the way it had been before the war. Secondly, the new Middle Classes, industrialists, businessmen, professional people, small landowners and writers and thinkers, who were generally moderate in their demands, but wanted to make a new start with a mildly democratic government, which would include themselves in its ranks. They wanted to see the end of elite rule by Squires, and of authoritarian rule and imposed political and religious faiths. They did, however, want to keep the lower classes in their place. But the lower classes were in fact a third group rebelling against the Third Empire, and they were much more extreme in their views. They demanded far greater equality for all, and in some cases sought the replacement of the Empire by a Republic. This demand sent a cold chill down the backs of both other groups, and opposition to it was one area in which they found common ground. There was of course a fourth power in the land, a very strong one at this time, the Army. Most of it was still on the fronts fighting the enemy, but increasing sections of it were left behind to enforce internal security. As we have seen, there was already some disorder within the middle and lower ranks, which sometimes tended to support the rebels and rioters. The leaders now also flexed their muscles, and forced the Succession Council to come to a decision about a new Emperor. In December, they persuaded it to install Riuden, a slightly liberal Squire, to be supported by a Reform Council. Meanwhile, the wars went on, and on two fronts they led to the victory of Atlantis and her allies within the year. The first success was against Ughrieh. By March, the Ughans were in a desperate situation. Two Gestskalland armies of over 20000 men were at the gates of the capital, Gargros, and to the east, devoid of defences, numbers of nomadic tribes were pushing into Ughan territory. East of the Gestes, but still west of the Gestix Mountains was an Atlantean army of 70000. To defend itself, the Ughans had over 80000 men against Atlantis, but only 140000 against the NE Empire, with other garrisons scattered around the country. Within two months, Gargros had fallen to the Gestskallands after a fierce final battle, but already the country was disintegrating. Southern areas had thrown off their allegiance to Emperor Tjaidon, and had made an armistice with Ughrieh. In the north, Tjaidon, having fled his capital with the court, was deposed, and soon murdered. Atlantis and Gestskallandieh had previously agreed to make a joint peace settlement, and insisted on a formal Ughan surrender. But the trouble was that it was no longer easy to work out with which party peace should be made. Moreover, the two victors had hardly agreed amongst themselves on the peace terms, as Atlantis had far smaller armies in the field than the Gestskallands, who were indeed in possession of the Ughan capital. Peace was agreed in June, but the peace terms were haggled over for months afterwards. The victors had long intended to split Ughrieh up as unified country, each taking portions either as outright annexations or as zones of control. This scheme was facilitated by the fact that the old Empire was splitting up of its own accord after April. Three separate kingdoms, north, central and south, had appeared, which in fact partly reflected the Ughan situation before unification after 710. The capital, Gargros, with Tjaidon’s successor as Emperor became the central section. Atlantis took control of the area immediately east of the Gargros mountains, which she already occupied. But after much discussion and controversy, she did not annex it as such, but left it as one of the Ughan kingdoms, under close Atlantean supervision. Gestskallandieh annexed much territory north and south of the river Gestes as far as the Yrullia Mountains, and also made sure she had direct control of the northern Ughan kingdom. Overall, Ughrieh was left in an utterly wrecked political situation, with most of her population at the mercy, directly or indirectly, of the two victorious powers. But Gestskallandieh had come out of the war at least as well off as Atlantis, partly because of the strength of her military position at the time of victory, and partly because Atlantis was increasingly preoccupied by her internal political divisions. Victory over the Ughans was followed in September, by the surrender of Skallandieh. As with Ughrieh, it was clear by the start of 749 that Skalland defeat could only be a matter of time, and Atlantis and Gestskallandieh began talking about their plans for the post-war settlement. Gestskallandieh was determined that she should take over and reunite the whole Skalland Empire again, and there was obviously no way Atlantis could prevent this. But while Brancerix was still in power, the Atlanteans insisted that Anauren should be reconstituted as part of the Atlantean Empire. The North Kelt area, mostly under Gestskalland occupation anyway should be split. During this period, the first half of the year, the Atlanteans retook the whole of former Anauren, but had problems advancing across the Ruphaio into Skalland territory. The Gestskallands were more successful in their progress westwards, and also into Kelt areas. After the fall of Brancerix, Atlantis’ position weakened, and she agreed in the end to annexing just the south of Anauren, up to the river Sulophaio, and leaving the rest as an independent kingdom. Arguments over the Keltish lands continued, and although Gestskallandieh had already occupied them, Atlantis insisted she still had a Province there called Nunkeltanieh. This fiction was finally abandoned in 752, when a comprehensive settlement made this whole area a theoretically separate Kelt state, under Gestskalland supervision. It fell soon after completely under Gestskalland control. Meanwhile the war rolled on to its end in September, with the Skallands finally surrendering to the two victors simultaneously. By this stage, Atlantean forces were penetrating into the Skalland homeland, and into the former Eliossien area, to which the Skalland capital had been moved in 747. VICTORY OVER BASQUECIEH STILL ELUDES ATLANTIS AND RABARRIEH Atlantean and Rabarran pincers slowly but inexorably closed in on Gosscalt’s armies throughout 749, and for all his genius, the writing was clearly on the wall by the latter part of the year. At the same time, Atlantis could see the initiative in the war gradually passing from her to the Rabarrans. Her armies were further from the heartlands of Basquecieh, and they were becoming outnumbered by the Rabarrans, in any case. Throughout the year 300000 Rabarrans were moving into the interior of the Basquec Empire from the south, 160000 of them advancing up the river Basquec towards Quachach and Bavcuat. Gosscalt had to spend at least half of his time dealing with this threat, and the mobile army, which he had employed to good effect against the allies in 748, had had to be sent south during the winter to deal with these Basquec armies. On the Gestes, his army of 110000 men, which he accompanied at first, made a slow and careful withdrawal to the river Vulcan in March, and then across it and the river Yallodairu, south-eastwards through Vulcanieh towards the Raziris mountains during April, May and June. Lingon’s Atlantean army, numbering 160000, followed the Basquecs, but was unable to bring it to a real battle. It was joined in due course by Buentel’s Manralian army from Atlaniphis, 100000 strong, which edged back its Basquec opponent (70000) up the Gairase. Meanwhile the Rabarran army on the Itheerdi, now 180000 strong, finally overwhelmed the opposing army of 110000 in a battle in August. The Basquecs were forced to retreat SE up the river Banchat, and the Basquec position in the Raziris Mountains was turned. Rather than try at this stage to deal with the Basquecs in Vulcanieh and Razira, who were left to the mercies of the Atlantean army, the Rabarrans opted to follow up the Basquecs right down to the Och Therult (Therult Mountains), which protected Bavcuat from the north. Seeing that he was now being left out of the chase altogether, Lingon suggested that Buentel should remain behind in Razira and Vulcanieh to deal with the remaining Basquecs there, to prevent them from interfering with the decisive battles further south, while he hurried on south, up the Gairase and Banchat, to join the Rabarrans in the Therult Mountains. This plan had the merit of giving the Atlanteans a presence, though only a minor one, in the final battles against Gosscalt next year. It also upset Gosscalt’s plans for the rest of the year, as he was sure that if he left a reasonable sized force behind in Razira and the Raziran Mountains, then all the Atlantean forces would have to stay behind to deal with them. This might then give him the chance of separating the two allies, and allowing him either to defeat them independently, or make peace with the Atlanteans separately from the Rabarrans. The Rabarrans moved up to the river Gedvox later in the autumn, but the Basquecs were able to prevent them crossing it for some time. Lingon, meanwhile, had hurried down the Gairase and round the Raziris mountains to join up with the Rabarrans in what appeared to be the final battles. The approach of the Atlanteans made the Basquecs abandon the river Gedvox and retire back to the Therult mountains by December. To the north, Buentel remained behind with some 100000 men and faced 80000 Basquecs and the forts in the Raziris Mountains. He sent a force round them to the south, to threaten Raziris itself, and protect Lingon’s rear (although he had an alternative line of communications now up the river Itheerdi, like the Rabarrans.)

Victory over the Basquecs, and the collapse of the Third Empire of Atlantis, 750 THE ADVANCE ON BAVCUAT, MARCH - APRIL 750 In the spring of 750, Atlantean and Rabarran armies closed in on the mountainous homeland of the Basquecs from every direction. In the south 180000 Rabarrans were moving up the river Basquec and the roads to the east forcing back an army of about 150000 Basquecs. By the end of April the Basquecs had entrenched themselves on southernmost end of the high ground which covered the whole area for about 200 miles to the north up to the source of the river Banchat, and also stretched some 120 miles west to the sources of the rivers Gedvox and Basquec and east to Quachach and almost to Votthac. Here the almost uncrossable Thecvach mountains separated the eastern road to Quachach and the western road to Tovduitth. At the beginning of March, the Rabarrans forced the Basquecs to split their armies: the largest force, about 70000 men moved some miles north-east to protect the capital, while a smaller force of 50000 men guarded the difficult route to Tovduitth. At first the Rabarrans sent 110000 men on the Quachach road and contented themselves with observing the Basquecs to the west with just 70000. Separately from them, 120000 Rabarrans were roughly parallel on the river Rualtacch pressing back about 50000 Rabarrans, with the eventual aim of reaching Votthac, which lay on the river about 50 miles east of the capital, Quachach. The latter armies were not involved in the great battles of April and May, however. In the north, Lingon with his 120000 Atlanteans began moving south up the river Banchat in March: he was accompanied by 50000 Rabarrans. The remaining 90000 men of the Rabarrans' Army of the River Itheerdi and commanded by General Seeldu, branched off south up the Gedvox. This was a plan agreed between the two commanders, which, it was hoped, would allow this southern Rabarran army to cross the pass through the mountains by the Gedvox and aim straight for Bavcuat. This was the base of the main Basquec army facing Lingon in the Therult mountains, where Gosscalt himself was now situated. This threat to his rear ought to make Gosscalt retreat south on Bavcuat and open the northern routes of the mountains to Lingon. At the beginning of April, the allied army under Lingon had reached the narrow mountain pass through which ran the direct road to Bavcuat. On a ridge of high ground in the middle of this pass was the defensive position held by the Basquecs in 661 during the First Battle of Quachach. At that time Ruthopheax defeated the Basquecs with a brilliantly conceived attack. This time Gosscalt again placed part of his army here, but as armies, because of modern weapons with longer ranges, could nowadays occupy wider fronts than in the earlier wars, he also occupied some of the hills to the west. Lingon had no intention of trying to break down this position. Due to entrenchments and the range of rifled weapons, it was much stronger than in the time of Ruthopheax. Instead some 70000 men moved west through other passes of the mountains near Cuaduitth, while Lingon just demonstrated in front of the main Basquec position. Gosscalt had placed forces to defend the other passes, but the allies managed to get through some of them. At the same time the southern Rabarran army had moved up the Gedvox and through the mountains on the road leading to Bavcuat from the west. Gosscalt realised by April 8th that his whole position had been turned, and reluctantly retreated slowly southwards, finally taking up a position on the high ground north of Bavcuat on the 14th. This position allowed him to command both the road to the south-east which led to Quachach, while also guarding the road west to the Gedvox and the route south-west to Tovduitth. Behind him lay the insurmountable peaks of the Thecvach mountains. The allied army followed warily, while the Seeldu's army from the Gedvox positioned itself on hills about 40 miles west of Bavcuat, and, crucially, in a rather isolated position. (Click on thumbnail)

GOSSCALT'S COUNTER-ATTACK AND THE RETREAT OF THE ALLIES TO CUADUITTH, APRIL 17th - 23rd Gosscalt realised as he retreated on Bavcuat that he had a brief chance of defeating the two enemy armies separately, and at then forcing them off to the north and west. At Bavcuat he had about 150000 men facing Lingon's allied force of 170000. About 40 miles to the west lay Seeldu's 95000 Rabarrans facing a Basquec army of 60000. Gosscalt quietly disengaged 70000 of the 150000 men at Bavcuat, marched them westwards on April 15th - 16th and on the 17th they smashed into the Rabarrans from the south-east. The Rabarran army was comprehensively defeated, losing 26000 men and sent reeling back north-west. This was away from their communications down the Gedvox and into the forested area around the edges of the Therult mountains. Meanwhile the Basquec army turned round and marched back eastwards on the 18th, this time aiming to join the main army in an attack on the allies in front of Bavcuat. In this Battle of Bavcuat, on 19th April, the Basquecs were again successful, inflicting 23000 casualties on the Lingon's army of 170000. In these two battles the Basquecs only lost about 15000 men in total. The allies were initially forced to retreat northwards up the road along which they had approached Bavcuat just a few days earlier. This was also Gosscalt's plan, as it would completely separate Lingon's army from the Rabarrans down on the Gedvox. Lingon, however, had managed to keep in contact with Seeldu and by the 20th decided to continue his retreat north-westwards, if possible, to the passes behind Cuaduitth. There he would perhaps remain within reach of help from Seeldu. But at the same time he sent 30000 Atlanteans to take up a defensive position in the woods east of the main north road, to prevent Gosscalt trying to break through in that direction. He then positioned a strong force on high ground to the west of this road, allowing him to slip his main forces north-west behind it. Gosscalt was unable to move this blocking force, despite several attacks, and thus it was that the allies avoided having to continue retreating north up the main road. The allies moved on towards the high ground near Cuaduitth, attacked continually by the Basquecs, who wanted to force them into the mountains away from the passes. All this time Seeldu had continued his retreat through the woods and round to the rear of the mountains. He managed to control the army, which had been virtually in a state of rout on the 18th. He even succeeded in losing his pursuers in this difficult country. Thus by the 21st he was climbing up the almost trackless Therult mountains and by the 22nd had passed them and lay only 13 miles from Lingon's army near Cuaduitth. Gosscalt had no inkling of the presence of this force.

THE BATTLE OF CUADUITH, THE SECOND RETREAT OF THE BASQUECS TO BAVCUAT AND THE ADVANCE OF THE RABARRANS IN THE SOUTH, APRIL 23rd - 28th Lingon had about 120000 men defending his position at Cuaduitth, facing about 130000 Basquecs. The Battle of Cuaduitth raged from late on the 22nd and on into the 23rd, with Lingon being forced gradually back into the mountains and through the pass. But about 2pm, Seeldu emerged from the north-west and smashed into Gosscalt's left flank with about 45000 men. This decided the battle and the Basquecs were forced finally to retreat back on Bavcuat. They had lost as many as 28000 men, as against the allies' loss of 16000. The final Basquec offensive was finished and only complete disaster lay ahead of them now. (Click on thumbnail) Meanwhile communications remained difficult between the Rabarran armies in the south and the north. Messages between the two, even using the newly invented electrical telegraph, often took over a week. It was easier for the Basquecs, and Gosscalt had at the beginning of April ordered the small army defending the western route from the south to Tovduitth to be prepared to pull back northwards, so that it could, if necessary, join in his planned manoeuvres against Seeldu's army. The eastern army, which was acting as a defence of Quachach against an advance from the south, was told to stay put, sending some men to Quachach itself, so as to prepare defences there in case they were needed. The Rabarrans followed up the Basquecs in the west, as they slowly retired towards Tovduitth. The Rabarran command had originally wanted to throw their main forces straight on Quachach in the east, but this route was extremely strongly defended. As the Basquecs in the east were obviously retiring towards Tovduitth and perhaps beyond, it was agreed to concentrate 110000 men to follow up this army, leaving just 70000 to face an equal number of Basquecs south of Quachach. Gosscalt retreated back towards Bavcuat, but as he did so, Lingon moved the 30000 Atlanteans that had been in the woods defending the direct road north, to strike the east flank of the retreating Basquecs. This they did on April 26th, and with help from the main army, forced the Basquecs to the east, away from Bavcuat and the main eastern road leading to Quachach. Gosscalt tried to counter-attack in order to regain his route to Bavcuat, but failed in this attempt on April 27th and his army began to show signs of panic. At this point he made a fateful - and fatal - decision not to try again to force his way to Bavcuat and the eastern route, but to continue his retreat south-westwards towards Tovduitth. He hoped to join up with the army down there, and throw the joint force against Lingon's army. He assumed this would have split up, part making directly for Quachach, and part following him. THE BASQUECS' RETREAT AND THE SURRENDER OF THE BASQUECS AT TOVDUITTH, APRIL 29th - MAY 4th Gosscalt continued to retreat to Tovduitth, where the route narrowed between hills to east and west. By the last week in April the southern Basquec army had already reached this position, facing south towards the Rabarrans. Gosscalt hoped to pick up some of this force, and throw himself against his pursuers. But now everything went wrong. Firstly Lingon followed Gosscalt's army with nearly all his armies, leaving only a small force of Atlanteans at Bavcuat to watch the road south-east to Quachach. Then he managed to edge his troops up on to the hills to the east of Gosscalt's army. Equally the southern Rabarran army had forced the Basquecs off the westernmost hills at the Tovduitth gap. The result was that Gosscalt's Basquecs became increasingly hemmed in the valley, with the allied army to the north and east of them. To the south, the other Basquec army was being pushed north, although a part of it still held the eastern hills. The day of decision came on May 4th. The Basquecs were surrounded on all sides - Gosscalt and a small force of some of his southern army managed to escape into the almost pathless wilds of the mountains to the east. (8 days later Gosscalt and a few others finally reached Quachach.) But the majority of the Basquec armies surrendered to the Atlanteans and Rabarrans by the end of the day. This Battle of Tovduitth involved the surrender of about 155000 Basquecs to a force of 280000 Atlanteans and Rabarrans. THE ALLIED ADVANCE ON AND STORM OF QUACHACH, MAY 8th - MAY JUNE 23rd It took a while for the allies to sort themselves out and deal with the huge number of prisoners they had garnered, but already on May 8th, 100000 men began the march back to Bavcuat and then on round to Quachach, the capital of Basquecieh. Gosscalt's whereabouts were unknown to anybody at first and when news of the disastrous battle at Tovduitth reached the Basquec authorities in Quachach, they soon began to consider seeking terms for ending the war. However Gosscalt turned up on May 12th and immediately began arranging the defence of the capital. By May 16th, the allied army had reached Bavcuat and soon began moving on Quachach. The Basquecs had about 40000 men left to defend the capital, plus the army of 70000 facing the Basquecs to the south. Gosscalt hastily pulled this army back to hold the hills surrounding the city, which was situated deep inside a sort of cleft in the mountains, easily defended from every direction except the east. However 110000 men could have little chance against the 300000 allied troops which would eventually be in a position to assault the city and its defences. By the end of May, these allied forces had reached the city and were soon able to force the enemy off the hills surrounding it. The allies demanded that Gosscalt should surrender himself and his forces but he refused. Indeed he called on his army on the Rualtacch, to the east, to come across and attack the allies in rear. But this army was only 50000 strong, and was being forced back all the time by 120000 Rabarrans. By the end of May it had reached Votthac, and rather than stand siege there or help Gosscalt's forces, it retired north-east across the river, with its commander declaring himself the new ruler of the country. He soon started peace negotiations with the Rabarrans. In the end there was no help for it but that the allies had to storm Quachach. This Second Battle of Quachach lasted ten days, from June 13th to the 23rd, and involved the most bitter street and house to house fighting in the Basquec capital. The Basquecs, inspired by Gosscalt, resisted with incredible tenacity, using every device and booby trap they could to defend their city. At the same time allied guns bombarded the city ceaselessly from the hills all round. Much of the place was reduced to ruins, and by June 23rd, over 55000 soldiers were casualties as well as perhaps 20000 civilians. The allies, who had about 240000 men fighting (90000 Atlanteans and 150000 Rabarrans), lost 60000 men (24000 Atlanteans and 36000 Rabarrans). Gosscalt was killed on June 22nd. On June 24th the remaining Basquec soldiers and members of the Government surrendered unconditionally. The Rabarrans, and for a while, Lingon, on behalf of the Atlanteans, discussed terms with the Basquecs in the capital and in Votthac, the second city, while the rest of the country gradually broke up into squabbling warlords. Later in the year, the Rabarrans reached a peace-treaty with the Basquecs, whereby they annexed a lot of territory to the west of the river Basquec, and in the far south, and maintained a considerable military presence in the country. The Atlanteans, due to the civil unrest to be described shortly, did not reach a full settlement till 751, and had little influence on the internal settlement of the country. The end result was a Basquec nation divided up into four territories, and a very strong Rabarran influence on the centre and western edge of the country. (Click on thumbnail to open)

At the same time as the war with Ughrieh was coming to its conclusion, Atlantis was becoming increasingly riven by political divisions at home. As described above, the Helvran nobleman Riuden had been installed as Emperor in 749 by a more liberal clique in the ruling class, backed by parts of the Army, which were acting on Internal Security duties. It soon became obvious that Riuden was just a pawn in the hands of the old die-hard Third Empire Squirearchy, and politics continued almost as before. Of special concern to the middle and lower classes was the Government’s policy of running down the large industrial and factory establishments, which had grown up because of the war, and the laying off of more and more workers. This was in addition to the gradual reduction in the strength of the Army, and throughout, an obvious determination to keep the whole Third Empire structure in being. All power was obviously to remain in the hands of the upper classes. As this failure of reform became clear during 750, there was a resurgence of the riots in the bigger towns. In many cases, these were also caused by a growing shortage of food. The Government’s attempts to restore the Class 1 and 2 landowners to the property, of which they had been deprived by the war and by local tenants taking unilateral action, met strong, armed resistance. By May, the government was losing control of large parts of the Empire. It wavered between some slight measures of conciliation (the role of "Loyalists" was finally abolished in April), and military force – more Army units were brought back from the frontiers of the Empire to the centre, to act as police and internal security. These were to protect landed estates and patrol the increasingly rebellious large cities. At the same time, foreseeing the end of the war within a few weeks, it ordered the reduction of the Army from about 750000 to 580000, and many of the losses would be from the officer class. BUENTEL’S REVOLT AGAINST THE GOVERNMENT, AND THE THREAT OF CIVIL WAR This growing turmoil reached a climax, as the armies and generals of the Empire began to take sides, for or against the status quo, and threatened to bring civil war down on to the Empire. The most significant event was the decision of Buentel to march to Cennatlantis in support of the middle-class demands for a complete end to the Third Empire, and the setting up of a new, more democratic regime. Buentel, it will be recalled, had long had democratic beliefs, and he had fallen foul of Brancerix in 746, at a time when he had been commander of the main, central Atlantean army. He was moved to Manralia, and replaced by the ultra-loyal Lingon. He now seized the opportunity of getting his revenge. It was at the beginning of July, only a week or so after a truce had been signed with the Basquecs, that he marched 65000 out of the 100000 men in his army in Razira and Yall. Thiss. back towards Cennatlantis. He left his second-in-charge to stay at the front with the remnants of his army. Lingon, who was technically in strategic command of Buentel’s army, was horrified, and accused him of desertion. Soon after, he realised more clearly that there was a political and military showdown approaching, and left the front to a subordinate, following Buentel with 80000 men of his own. This was at the end of July. This gradual disintegration of the Atlantean army from the frontiers, the paralysis for the next few months of any central political authority, and the political upheavals, which continued for at least another year, led to the complete collapse of Atlantean diplomacy. In other words, Atlantis was unable to take any real advantage of the collapse of her enemies at the end of the war, and left the way open for Rabarrieh, in particular, to secure great political advantages in the peace-treaty with Basquecieh. THE RIVAL ARMIES GATHER AROUND CENNATLANTIS Buentel realised he was facing strong opposition to his revolt. Apart from Lingon, with up to 180000 men in Basquecieh, there were several other armies, which were either hostile or at best neutral – none had come out in support of Buentel in July. In Yeldatlantis and Cennatlantis, there were at least 60000 men acting as police and Internal Security. On the river Gestes, and on the Ughan border, there were another 60000, the army, which had recently defeated the Ughans. Finally there was General Elthul’s army, 180000 strong, in the north-west, which had just defeated Skallandieh. Buentel was least concerned about the central forces, as these were split up into penny packets, guarding towns and property, and fighting a nascent guerrilla army, which wanted to overthrow the Third Empire on its own. Some, too, were at best lukewarm about fighting their fellow-countrymen. Uneasily supporting these rebels was the group of middle-class democrats, mostly in Atlantis, Cennatlantis, Gentes and Helvris, who had appealed to Buentel to support them. As he marched back, Buentel gathered up and recruited additional men, but also left up to 40000 behind to delay Lingon, when he had heard that he was following behind. Riuden and his government, within the city of Cennatlantis, now ordered the "Ughan" army to intercept Buentel, before he reached Cennatlantis. Buentel had crossed the Gentes at Vulcanipand, which made no attempt to resist him. He left a garrison of his men there to hold up Lingon, and moved north, intending to approach Cennatlantis from the east. He then came up against the "Ughan" force near Yellis on August 10th. After a short battle, there was a halt and a truce, and 30000 of the "Ughan" army came over to Buentel. The rest, he sent back to the frontier. Riuden now ordered the immediate suppression of all urban revolts, beginning with Cennatlantis, where some rebels had barricaded themselves into buildings. Loyal forces forced these to surrender or retreat to the south, where they were joined by up to 15000 other rebels, a mixed bag of disaffected, regular soldiers, and armed workers and middle-class citizens. Their mood was becoming increasingly bitter, because of a number of atrocities and massacres committed by the loyalist troops, when clearing the rebels out of Cennatlantis. Both sides were trying to win over Elthul’s forces in the north. Elthul had remained resolutely neutral hitherto, but had moved 70000 of his men southwards towards Cennatlantis in August, though without making it plain whom he was intending to support. Finally in September, he came out in favour of Buentel and the rebels. Buentel, by this time, was manoeuvring to the north of Cennatlantis, near Gilliso, and seized Gasirotto at the same time. He had 80000 men present, and was faced by about 50000 loyalists at Cennatlantis. There were also 15000 rebels facing them nearby. Also by this stage, Lingon had fought his way north to the Gestes, with some 70000 men. The manoeuvres of the rival armies in Atlantis, July - August 750

DECISION AT CENNATLANTIS – THE VICTORY OF THE REBELS Negotiations between the two sides went on throughout August and early September, but it was soon clear that Riuden was refusing to make any serious concessions at all. The rebels agreed on Sualofo Thildoyon as their candidate for a new Emperor, not without some misgivings from the more extreme democrats. They also agreed that the whole Third Empire structure should be dismantled by force. Buentel was now getting nervous about the approach of Lingon, and decided to bring matters to a quick conclusion. He crossed the Dodolla at Rundes, and approached Cennatlantis from the north. The loyalists came out to meet him, and in a hard-fought battle on September 25th, they were defeated, and forced back into, or through Cennatlantis. Buentel and the other rebel forces now completely surrounded Cennatlantis, which was occupied by Riuden and his government, and about 8000 soldiers. Negotiations resumed, but they still refused to submit to the rebels, fearing for their lives. Meanwhile, Lingon, unable to cross the Gestes at Vulcanipand, moved up its east bank, and crossed at Borepande, still holding a garrison loyal to him. By the end of September, he had reached the Burastoura. To counter him, Elthul now properly committed himself for the first time, and moved with 45000 men into Gasirotto and Sirottis. Riuden managed to smuggle a message out to Lingon, ordering him to come to their help at once. But the rebels intercepted it, and Lingon turned instead to deal with Elthul. Buentel continued to hesitate, and seemed to be trying to give the Squires as long as he could to surrender peacefully. He did not want to see Cennatlantis and its inhabitants consumed in a bloodbath. But matters were taken out of his hands. Egged on by Thildoyon, the rebel forces now attacked the enemy in the capital from the south and the west, daring Buentel to support them. They could not succeed on their own, and reluctantly Buentel committed a small part of his force to join them. The original document here describes vividly the dreadful end of the leaders of the Third Empire in Cennatlantis. The manoeuvres of the rival armies in Atlantis and the storm of Cennatlantis, August - September 750

Conclusion THE RESULTS OF THE WAR The Great Continental War had been by far the biggest and most destructive war ever fought on the Continent. It involved every nation surrounding Atlantis, and Atlantis itself, of course, for up to seven years of fighting. The one nation not involved was "Quendelieh", the Western Empire, whose territories now abutted those of Atlantis in Phonaria. Armies far larger than ever before were raised by conscription in all these countries. Atlantis had 1,400,000 men under arms at the maximum in early 747, out of a population of 35,000,000 (excluding areas occupied by the enemy – it was 76,000,000 in 743). Basquecieh armed 1,100,000 out of a population in the Basquec Empire of 38,000,000 at any one time; Ughrieh 750,000 out of 30,000,000; Rabarrieh 680,000 out of 18,000,000 (excluding enemy occupied areas); Skallandieh 600,000 out of 13,000,000; and Gestskallandieh 550,000 out of 11,000,000. Thus there were over five million men in arms at the high point of the Continental War, which, it should be remembered, involved essentially pre-industrial societies. Casualties were equally massive, and dwarfed anything hitherto, and every war that followed up until the Final Wars after 870. Atlantis lost over 550,000 fighting men killed, either by war or disease. Figures for the other countries are much less certain, but probably Basquecieh lost 500,000, Ughrieh 250,000, Rabarrieh 400,000, Gestskallandieh 230,000, and Skallandieh 350,000. Rabarrieh and Basquecieh had of course also been at war from 732 till 737, when they had lost another 100,000 between them (mostly Rabarrans). In addition to the major campaigns and battles, described in the account above, there were many other areas of "minor" fighting and skirmishes, which produced their own crop of casualties. Full-scale guerilla fighting took place against the Basquecs in the south and west of Manralia, and the Basquec occupied regions to the south. Similarly, there were incursions by nomadic and other small tribes into the extreme east of Ughrieh and Gestskallandieh from about 746 onwards and revolts by the North Kelts against the Skallands after 747. Furthermore there was considerable loss of civilian life in certain areas, especially those involved in guerilla warfare, and incursions by "uncivilised" tribes, but also between certain of the major combatants, whose feelings towards each other were particularly bitter. This bitterness led to frequent massacres and ill-treatment of civilians, and was particularly prevalent between Rabarrieh and Basquecieh in the areas of Basquecieh and Rabarrieh invaded by the other side. It also occurred in the parts of Dravidieh and Vulcanieh occupied by the Basquecs. Nearly as serious was the destruction to property in these areas and other regions fought over, such as Anauren and the edges of Ughrieh. Incidentally, Anauren, which disappeared as an independent country after the Skalland invasion of 744, was particularly badly hit by the war. Soldiers and civilians of Anauren suffered around 150,000 deaths during the wars, and terrible damage to property. With this as the background, it is hardly surprising that at the end of the war, all the combatants were prostrated, and most suffered, then or later, serious internal and political upheavals. Ughrien disintegrated as a united kingdom, and fell prey to civil war on and off after the 770s. Basquecieh collapsed into civil turmoil in the 760s. Skallandieh was swallowed up by Gestskallandieh, and Atlantis saw the collapse of its Third Empire, and narrowly avoided civil war thereafter. Only Rabarrieh and Gestskallandieh came out of the struggle more or less unscathed, but even in the case of Rabarrieh, trouble occurred some years later, when its whole social system was revoultionised by a religious revival. THE EFFECTS OF INDUSTRIALISATION The Continental War began virtually as a pre-industrial war, but throughout its course, the fruits of industrialisation and innovations profoundly affected the weapons used in the fighting. The fighting-men of all the combatants began in 743 with a small number of firearms, rifled or not, and a mixture of artillery types. By the end of the war, nearly everyone was fully equipped with rifles and rifled artillery. This greatly altered the way battles were fought, for the increased firepower and range of the new weapons, made the close-order tactics and infantry and cavalry charges of earlier warfare far too costly. So soldiers dug trenches, and both sides often faced each other in stalemate, as at Cennatlantis in 745, and Atlaniphis later on, as well as in south Anauren and on the borders of Gestskallandieh and Skallandieh. Only the ability to engage in wide turning movements enabled a war of movement to be resumed by Atlantis, Rabarrieh and Gestskallandieh after 747. Attempts were made, especially by Atlantis and Basquecieh, to break the deadlock by providing additional protection for the infantry from armoured transports with steam propulsion, but although this would be the way of the future, it had little success, at least on land. At sea, however, the new industrial processes which produced armoured protection and steam-power were much more successful. Before 743, parts of all navies were still wooden and powered by sail. Larger breech-loading and rifled guns had, however, appeared on many ships in almost all navies. The Basquecs had led on this, and in the 730s also adapted a number of mostly smaller ships with iron armour plating, and, in some cases, with steam-engines, as well as large rifled guns. These ships had some success in the 732 war against Rabarrieh, and again after 743. Atlantis, as well as Skallandieh, quickly copied these Basquec initiatives in the years running up to the War, thereby finally rendering the ban on new technology a completely dead letter. The fighting in the south led to initial Basquec victories, largely due to their superiority in ironclads, steam-power and the size and power of their gunnery. However, the allies caught up later. In the north, Skallandieh had deliberately built a small but very advanced navy before 744, with iron armour and steam-power. This helped it to its initial overwhelming victories against the lees well-prepared Atlantean ships in the area. Anauren, too, had some armoured ships, which were captured by the Rabarrans in 744. Again, later, Atlantis caught up with its rivals in this region, and by 750, all its major ships were armoured and powered by steam. To read about the Fourth Empire of Atlantis, click on Fourth Empire- (1) 750 - 761

|