|

Home Page

Discovery of Atlantis

First Empire-(1) to 261

Second Empire- (1) 361 - 409 |

|

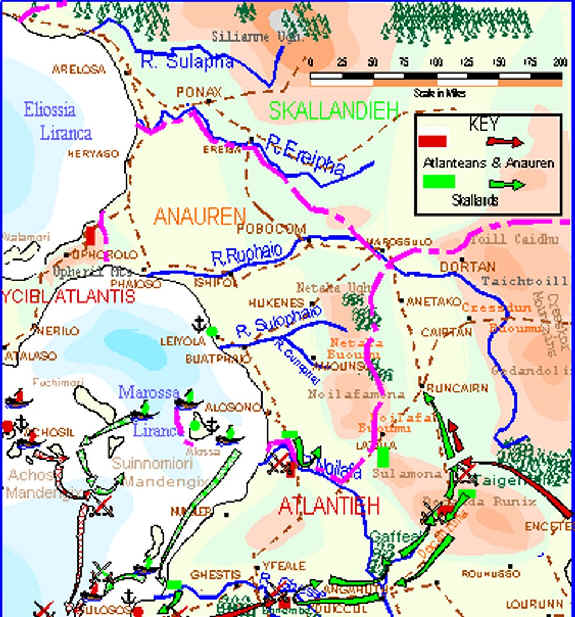

746: The year of decision THE BATTLES OF GENTIS AND RUNNATES: THE CLIMACTIC ATTEMPTS TO BEAT THE ATLANTEANS IN THE CENTRE The year 746 dawned with the Basquecs, and their allies the Ughans and Skallands, still facing an intransigent Atlantean Empire. But despite a series of disappointments and narrow failures in 745, Gosscalt still thought he could force the enemy to the negotiating chamber by inflicting one or two more decisive defeats on them. There is little doubt that this was still possible, though not for much longer, as Atlantis was really gearing up to total war, and the size of her armed forces would decisively overtake Basquecieh’s during 746. Gosscalt decided that the siege, or blockade of Cennatlantis was not getting him anywhere, and he decided to abandon it in favour of a campaign of manoeuvre in 746. In March, he withdrew most of his forces from Cennatlantis, and marched north to Gasirotto, hoping to force his way between the two lakes, seizing or bypassing the fort, and then moving south-west against the flank of the Atlanteans around Cennatlantis. He also tried to co-ordinate this attack with contemporaneous ones by the Ughans towards Runnates, and the Skallands against Atlantis itself. The Ughans and Basquecs did manage to move almost at the same time, but it was very difficult to communicate at all with the Skallands, who were virtually cut off from the Basquecs, and in the event, they did not attack for another two months. It could indeed be argued that Gosscalt should have made more effort to persuade the Ughans to join his own armies in a combined attack via Gasirotto, rather than allowing them to move off at a tangent to Runnates. But the Ughans were throughout the whole war, extremely unwilling to see their armies act in a sort of junior role to those of the Basquecs, and they frequently went their own way. The attack on Gasirotto took the Atlanteans by surprise, and the city fell after a brief siege and assault. The army had already pressed on westwards, at first trending towards Ancahouth. But the Atlanteans gathered their defences quickly, and a relatively small force positioned itself east of Gentis. Seeing this as a more serious threat than it really was, Gosscalt moved the bulk of his forces west against this army. A first battle, on April 3rd pushed back, but did not defeat the Atlanteans. A back-up for the Atlanteans now rushed up from the Cennatlantis front, but instead of attacking the smaller Basquec force north of Ancahouth, it joined the Atlantean force now west of Gentis. Strategically, this seems a surprising move for the astute General Buentel, but he believed that Gosscalt would expect him to attack from the south, and so wanted to do something, which would be more unexpected. Gosscalt hoped to beat the Gentis force quickly, and then turn south on the enemy there. In the Battle of Gentis on April 5th, 125000 Basquecs tried to break a defensive force of 50000 Atlanteans at first, later rising to 102000. Gosscalt was reduced to straightforward frontal assault, which at first had some success, but then was overwhelmed by the Atlantean reserves gradually fed into the battle as they arrived. After suffering over 19000 casualties, the Basquecs admitted defeat, and leaving a blocking force at Gasirotto, retreated east, to Sirottis. The Battle of Runnates, April 27th - 28th. Meanwhile, the Ughans had finally wound themselves up to advance westwards as well, acting as a protection to the Basquecs’ right flank. With a force of 90000 men, they attacked the opposing smaller Atlantean army near Micazzo, which retreated rather precipitately as news arrived of the Basquecs' advance past Gasirotto. The Atlanteans retired to a strong defensive position at Runnates, behind the river Chakratoura. They hold the town itself, behind the river in the centre, behind which are hills trending south-westwards away from the river. The Ughans made a frontal attack on the town on April 27th, while other corps crossed the river a few miles to the south onto the plain. The Atlanteans retreated to the strong position of the hills in rear, abandoning Runnates, save for a small garrison left behind. The next day the Ughans forced their way through Runnates and on April 29th unsubtly tried to storm the hills immediately behind. After a whole day of fighting, they give up the attempt. They now try to turn the Atlantean right flank, and march off to seize these hills the following night. However, the Atlanteans have anticipated this move, and have a small force already guarding these heights. Other troops are rushed over from the north, and although the Ughans retain a footing on the hills at nightfall, they again fail to defeat the Atlanteans: indeed, they themselves are now seriously weakened by their heavy losses of over 17000 men. The Battle of Runnates, April 29th The Atlanteans now seize the chance for a decisive counterstroke. Early next morning they strike with their left wing into Runnates, which had been left with a minimal defence when the Ughans moved most of their forces across to their left. Runnates is taken, and the Atlanteans now move to the right to strike the Ughans on the hills in flank, while smaller forces crossed the river. However, the Ughans had already started to withdraw the night before. But they were seriously mauled as they moved back over the river by having to ward off these flank attacks. Once over the river, they again had to run the gauntlet of the Atlantean cavalry and infantry. Thus the Battle of Runnates (April 27th-30th) was in the end a bad defeat for the Ughans, who lost in all some 26000 men. In a closely pursued retreat, the Ughans were chased back to Micazzo, and then when the Atlanteans threatened to turn their right flank, they retreated further back to Dravizzi. The Battle of Runnates, April 30th Greatly disappointed at these defeats, Gosscalt now moved south to a position around Gilliso. There was very little further fighting in the centre for the rest of the year. The Atlanteans were content with defending what they had won and building up their forces, while fending off the serious attack in the west by the Skallands. Gosscalt now handed over command of this army to General Guentich (usually "atlanteanised" to "Guentic"), a capable but uninspired man, who would soon prove no match to Atlantis’ General Lingon, who was to take over Buentel’s position in 747. Gosscalt now moved back to Basquecieh for several months to deal with political troubles and military reorganisation, and to concentrate on the increasing threat by Rabarran and Atlantean forces in the south. SKALLANDIEH’S AMPHIBIOUS THREATS TO ATLANTIS Skallandieh planned what it hoped would be a decisive series of amphibious attacks against Atlantis, starting in May. These, it was hoped, would end ultimately in the capture of the old capital, Atlantis, itself. They would coincide with land assaults towards the Gaffeal, and across the rivers in Marossan. The campaign began with further attacks by the Skalland navy, which was at present showing itself more than an equal for the Atlantean fleet. The latter’s lack of wartime experience for many years had been very apparent. The attacks were against the main Atlantean base at Achosil, and were intended to distract the enemy from the amphibious force, which then slid down the coast past Nundler to the river Bore estuary. There, on May 27th, it landed a large army, which immediately marched towards Atlantis. News of these events prompted the Atlanteans to order the Achosil fleet southwards to defeat the enemy navy off the Bore, while the relatively small Atlantean fleet at Atlantis stayed to defend the city. (This fleet was normally at the naval base of Sulosos, but following the Basquec naval scare in 745, when it looked as if the Basquecs might move on Atlantis itself, this fleet had been moved to Atlantis, where it had stayed ever since. The Skallands were aware of this, which made their amphibious landings much less risky than they would have been, had the Atlantean navy still been stationed at Sulosos).

The defeat of the Skalland invasions of Atlantieh, 746 The diversionary Skalland fleet had, however, already been engaging the Atlanteans near Achosil while the Bore landing was happening. After some inconclusive fighting, it pulled away to the south, nearer the Bore fleet, where the Atlanteans followed it. In a lengthy series of manoeuvres and battles the Skallands came off worse, and were forced to retire north-eastwards. The Atlantean fleet now carried on south. Meanwhile, the Skalland invasion fleet, having sent the transports back north, had moved on past Sulosos, where it had defeated the fleet from Atlantis on June 6th. But the Achosil navy now arrived, and manoeuvring so as to link up with the remains of the Atlantean navy, inflicted a crushing defeat on the Skallands at the Naval Battle of Sulosos on June 15th. (For a detailed account of this battle, with maps, see the section on the navy during the Continental War, which is part of the general article on the Atlantean navy: The Atlantean Navy ) Meanwhile on land, the Skalland army, landed at the Bore, crossed the river, took Sulosos, and forcing back two small blocking forces, reached the very gates of Atlantis. Every last Atlantean was now put into the firing line, and at the Battle of Atlantis, on June 5th, the Skalland force was defeated and virtually surrounded. Out of 33000 men, only 7000 escaped death, injury or capture. To compound the Atlanteans’ troubles, the Skallands launched other attacks at the beginning of June. One army tried to cross the river Noilafa, and move to link up with the amphibious force on the Bore. In fact, it was unable to force the Atlanteans’ defences, and had to retreat back across the river. At the same time, to the east of the Netaka Mountains, a second army forced the Decabrumu pass in the Decanda Mountains. These marked the border between the Province of Naokeltanieh, now wholly in Skalland hands, and that of Cennatlantis, from which there were straight marches south on Cennatlantis, or west into Yeldatlantis. There is no doubt that at this stage, the beginning of June, the very existence of the Atlantean Empire seemed to lie on a knife-edge – for the fourth time in a few months, following the Basquec naval expedition in 745, and the Basquec and Ughan attacks beyond the central lakes earlier in 746. In reality, as these various offensives were not simultaneous, the Atlanteans, even if defeated at first, would almost certainly have been able to fight off each of them individually, using their immense resources scattered on other fronts throughout the Empire. Even so, a continuous series of setbacks and defeats like this would have gradually weakened Atlantis and made it far more likely she would sue for some sort of truce or formal peace. The Skalland attack began well, and after forcing the Decabrumu, moved around the Gaffeal (literally "old wood"). The army crossed the river Rollepp, taking Angahuth, and moved westwards. But already the Atlanteans had defeated the Bore amphibious force, and the attempted crossing of the Noilafa. The Atlantean defenders fell back toward the Borfembe, where they were reinforced by units from both the other, victorious Atlantean armies. On June 14th, as the Skallands tried to force their way into the Atlantean position in the woods, these reinforcements turned the Atlantean defensive into an all-out attack from front and flank. The result of this Battle of the Borfembe was the narrow defeat of the Skallands. Out of an army outnumbered in the end by 65000 to 55000, they suffered 10000 casualties. The army was forced to retire, the more so as more Atlantean troops were arriving to press their retreat. They went no further than the Gaffeal, where, expecting reinforcements, they stood and dared the Atlanteans to attack them there. The Atlanteans to the west realised the strength of the new enemy position, but General Elthul had other plans. He requested and was granted the shift across of 35000 men from Runnates, led by General Lingon. Two months earlier, this force had helped defeat the Ughans, and it was now in reserve. The Skallands half expected something like this, and decided to retreat further to the Decanda Mountains. However, the Runnates force was directed north of these mountains, and hit the Skallands in flank, just as they were emerging from the Decabrumu pass. This resulted in an absolutely decisive defeat for them, and the remains of the army fled back to Runcairn by the middle of July. Thereafter, there was little further movement for the rest of the year, but the initiative had now decisively passed to the Atlanteans. THE WAR IN THE BALANCE ON OTHER FRONTS These were the most decisive campaigns of the year, but fighting was taking place elsewhere, throughout the continent, and here too, the balance was turning. In the north, Gestskallandieh stayed on the defensive in the west, and started to shift her forces east to deal with the Ughans’ incursions into her territory over the past year or so. Later in the year, following her defeat at Runnates, and with her morale lowered, Ughrieh was attacked by Gestskallandieh, and her forces ejected from her territory, and thrown back across the river Gestes. In the south, the removal of the Basquec navy to the Helvengio at the end of 745 made it much easier for Atlantis and Rabarrieh to regain control of the southern seas. Rabarrieh was now receiving considerable help – military and naval – from Yciel Tuaince Mandagge (the Far South Continent), whose rulers were much in sympathy with those of Rabarrieh. The fleets of Atlantis and Rabarrieh, with this help, were able to break the Basquec blockade, and defeat them at the Second battle of the Siphiyan islands. They then retook those of the Siphiyan islands, which were in Basquec hands, and in August, concentrated their forces and advanced into the Siphiyans Mountains. They made a few tentative attempts to force back the Basquecs from here, but were not very successful. However, they started to build up during the winter a really significant base at Siphiya, and a large, offensively minded army. This was to be part Atlantean and part Rabarran. At the same time, the resurgence of Rabarran fortunes continued with further operations in the delta of the river Kataba, and the blockade of some Basquec ports. Finally, what happened in the Helvengio, where the great Basquec fleet had been forced into hiding in the Gairase estuary the previous year? It remained impotently here for the whole year, loosely blockaded by the Atlanteans, and emerging only twice, for a couple of ineffectual skirmishes. The Atlanteans also isolated the enemy forces on Giezuat island, and later in the year landed and took their surrender almost bloodlessly. They also continued to land reinforcements at the mouth of the river Sheinteph in Manralia, advancing south a little way, but aiming at a real offensive in 747.

Victory abroad and rebellion at home, 747-750 THE SHIFTING BALANCE OF FORCE AMONGST THE BELLIGERENTS If the year 746 had seen the turning-point in this great war, 747 saw a definitive shift in fortune in favour of Atlantis and her allies. There were virtually no more great advances by their enemies: on the contrary, they began counter-offensives, which grew more and more overwhelming over the next three years, leading to universal victory by 750. How did this happen? Firstly, Atlantis and Rabarrieh were rapidly increasing the size of their armed forces, which, in Atlantis’ case, reached their maximum size in 748. This was achieved by the growing efficiency of the organisation of the war, the militarisation of population and resources, and the favoured status these two nations had achieved in the eyes of Yciel Tuaince Manage and the Western Empire. Secondly, the armies themselves were now better trained, and were led by better generals. For example, in early 747 Atlantis had General Lingon in charge in Cennatlantis, Buentel in Manralia (moved from Cennatlantis), and Elthul and Giben respectively to command the land and sea counter-attacks against Skallandieh. All these were talented, efficient and experienced generals, and in the cases of Buentel and Elthul, touched with genius. Finally, of course, the new technology, which had given Rabarrieh such an advantage in 743, was now in everyday use in nearly all the combatants armies, most especially Atlantis. Indeed, Atlantis was able to exploit her industrial base, which Brancerix was encouraging, to invent new and improved weapons – mines, explosive shells, balloons, steam-powered transport, though most of these were very experimental, and had little overall effect on the war. Strategically, too, Atlantis and her allies were able to exploit their new superiority in sea-power to make amphibious landings or threats of landings against their enemies. THE DEVELOPMENT OF ATLANTEAN MILITARY POWER Atlantis had developed and improved her military forces in various ways since the start of the wars. Full conscription since 745 meant that she could field forces of over 1110000 men in 747, rising to a maximum in 748 of 1400000. Individual armies (PUEGGISIX) were grouped into Army Groups (BORPUEGGISIX), each with 3 to 7 Armies. Each Army Group (or effectively Front) had its own Grand General (Elthul in the west, Lingon in the Centre, Buentel in Manralia). The PUEGGISIX, about 24000 strong in 743, and divided into 4 CENNDARCOYIX, (literally "NEW THIRDS") were reduced to about 20000 by 746, and their sub-units rechristened as THEINULPUEGGISIX (literally "QUARTER ARMIES"), later simply THEINUIX (or "QUARTERS"). Also another unit was created between those of THEINUIX (5000) and PUONDIX (480). This was the DARCOYO of 1200, while the PUONDIX were reduced in size to about 200. In 749 these DARCOYIX were also given new names – OCHOSSIX, as a deliberate reminder of Second Empire times. Cavalry were also reorganised, and new, larger, independent cavalry armies were created after 746, to carry out wide manoeuvres and make the rapid advances, which were such a feature of the later stages of the war, compared with the trench-bound middle years. Thus pistol-armed, cavalry THEINUIX, of 4000 –5000 men appeared, ultimately under the control only of the BORPUEGGIS. They were then often combined into cavalry PUEGGISIX. Changes in tactics and weaponry even by 747 were considerable compared with 743, and the changes continued up till the war’s end. We have already spoken about the new, larger cavalry units. Infantry formations grew looser, with heavier firepower (breech-loading rifles for all soldiers). Men spread out more, and skirmishers were used more consistently. As far as artillery was concerned, all mechanical types soon vanished, in favour of rifled breech-loaders and howitzers. As many as 5 or 6 guns per 1000 men were deployed. Finally transport and support: the system which Ruthopheax I had built up, and which had declined throughout the Third Empire, had to be laboriously re-introduced during the war. This time, horses and carts were supplemented on a small scale by steam-powered vehicles. There were also changes in Atlantis’ military leadership, as we have already noted. Hitherto, overall leadership of the war had rested with the Emperor and Officers of State, part of which now constituted a War Council. There was increasing pressure to appoint a military man as overall Commander-in-Chief, but Brancerix resisted this, determined to keep this post in his own hands, as indeed he did throughout the war. Similarly the War Council, and the Officers of State remained traditional Imperial nobles, although there were some changes amongst them. But in the field, increasing numbers of commanders at the highest levels were being replaced by more effective, lower-class men. And of course, the back-up to the whole war effort was an increasingly large and efficient industrial base, also led by middle class factory and workshop owners. The command of the war against Skallandieh was given, on land, to General Elthul in 746, who narrowly managed to survive the great Skalland attacks on Atlantis. In the years to come, he would show his true colours by leading the great counter-attack against Skallandieh. In this he would be ably seconded by the new Admiral of the Achosil fleet, Giben. More controversial were the changes to the commands in Cennatlantis and Manralia. General Buentel had admirably succeeded in holding off all Gosscalt’s attacks on Cennatlantis since 745, but in the eyes of his superiors, he then seemed to settle down into inactivity for much of 746. Brancerix was desperate for a counter-attack to free Imperial soil of the Basquecs and Ughans. However, the removal of Buentel turned into a political matter as well at this stage. Buentel was of Class 3 background, and had never made much secret of his dislike of the Imperial regime. He expressed this normally by demanding more lower class, and hence, to his mind, efficient commanders on his staff. But then, at the end of 746, he went much further, and asked that he himself should be created overall Commander-in-Chief of the war. This was too much for Brancerix, and he ordered his removal from post, and transfer to Manralia to head the planned offensive there. This was an important position, but could in no way compare with Buentel’s former post. Brancerix also knew very well with whom he wanted to replace Buentel. He chose General Lingon. Lingon, as an army commander, had fought very well against the Basquecs ever since the start of 745, and had contributed greatly to the defence of Cennatlantis. He was later the commander of the small group of armies under Buentel’s command, which had rushed up to reinforce his defence at the Battle of Runnates against the Ughans in 746, and had then been moved west to defeat the Skallands at the Decabrumu Pass. Thereafter he had harried the Skallands in small-scale warfare on his own initiative. His appointment was one of Brancerix’s most inspired choices, and his leadership during the next two or three years was to contribute decisively to the utter defeat of the Basquecs. In this, he was to reveal talents bordering on genius for strategical warfare, and was able to outwit even Gosscalt. But at the time of his appointment, Lingon’s real virtue in the eyes of Brancerix and his colleagues was his impeccable Class 2 background, and his devoted and vocal support of the traditional Imperial regime. This had indeed led him into a number of conflicts with Buentel, who had been pleased to lose him to the Skalland front in 746. In four years’ time, in fact, the conflict between the two men would become not just a verbal, but a military one.

DEFEAT AND VICTORY: THE RECOVERY OF CENNATLANTIS At the start of 747, on the central front, the Basquecs had two Armies near Atlandravizzi in the Crolden Hills (150000), and another two south of the Cresslepp at Helvris (70000). Gosscalt himself had returned to Atlandravizzi by the end of February. On the other side, the Atlanteans had concentrated nearly all their forces around Cennatlantis – about 200000 -, leaving only about 60000 men west of Helvris. General Lingon started off in his new job with a plan, which was just asking for disaster, when faced with someone like Gosscalt. Determined to carry out an attack as soon as possible, Lingon left about 80000 men at Cennatlantis, to guard against an attack from the south, and launched the rest of his force directly eastwards, aiming to seize Giestisso and threaten Gosscalt’s line of communications with Borepande. He knew this would make the Basquecs emerge from their defences on the Crolden Hills, and he intended then to defeat them in the open. In the event, it was a case of the biter bit. Gosscalt did emerge, but threw a force of 120000 men on to Lingon’s flank and communications, before the Atlanteans were prepared. Although still just outnumbered by the Atlanteans, the latter were badly defeated at this Second Battle of Giestisso on March 23rd, and retreated quickly back to Cennatlantis. Meantime, on Gosscalt’s orders, his army at Helvris had moved up the Cresslepp to threaten Cennatlantis from the south. However, the Atlanteans had held off this attack, and on the return of the main Atlantean army from Giestisso, the Basquecs abandoned their attacks, but remained in the area of Giezat, north of the Cresslepp, which was in their rear. Lingon now pulled himself together. He spent a month reorganising his armies, which were now concentrated at Cennatlantis. He began operations by throwing 120000 men at the Basquec 60000 south of the city. These were utterly defeated at the Battle of Giezat on April 27th, and forced back to Noccsat. They still maintained a hold on the city of Helvris, however. Then, in the middle of May, as Atlantean armies were approaching Atlaniphis in Manralia, Gosscalt decided that he must be on the spot, and travelled south. Before he left, he warned General Guentich, who was left in command of the army, to remain on the defensive. However, not realising the true skill of Lingon, he added that if the Atlanteans again attacked east, he could, cautiously, try to manoeuvre against them. At the beginning of June, Lingon moved most of his force of 170000 eastwards, precisely to try to make the Basquecs move out against him. But then he detached a force of 70000 men off to the north to catch any such enemy move in flank. Guentich fell completely into the Atlantean trap, and advanced westwards with 130000 men. The Atlanteans deliberately fell back cautiously before them to the defensive position at Snattarona. Then, on June 7th, the detached force crashed down into the Basquecs from the north. At the Third Battle of Snattarona, the Basquecs were decisively defeated, losing 45000 men, including 25000 prisoners. Guentich was forced back south-eastwards away from Atlandravizzi, and in a brilliant pursuit, Lingon forced him to retire right back to Borepande by the end of July. At the same time, the Atlantean forces west of Helvris besieged and took the city, while in August, a force marched westwards around the south of Lake Trannolla. This forced the Basquec army at Noccsat to retire gradually towards Vulcanipand. REARWARD MOVEMENTS BY THE UGHANS Lingon made no serious attempt to remove the Ughans from their position at Dravidos, until his northern army had received replacements for the force, which had been sent against the Skallands the previous year. In fact, the attention of the Ughans was being increasingly diverted to the north, where the Gestskallands were continuing to gain ground. They had 200000 men in the field against the Ughans’ 160000. They sent a force into the Diefillen, and by August this had retaken Fembepand. Other armies crossed the upper Gestes and threatened the heartland of Ughrieh. At this stage, Atlantis had 90000 men opposite what had been 110000 Ughans at Dravidos and Dravizzi, but were now only 85000. In a carefully co-ordinated plan, Lingon moved his northern army against Dravizzi, while part of his southern force (60000) swung north-eastwards from Atlandravizzi across the Thyggis towards the communications of the Ughans at Dravidos. There was a fierce battle to take Dravizzi, but the Dravidos force, after a half-hearted lunge at the Atlanteans, retreated behind the Gestes. ATLANTIS’ RECONQUEST OF MANRALIA AND THE DEFEAT AT ATLANIPHIS South of the Helvengio, both Atlanteans and Rabarrans undertook offensives, which made such progress as to sweep the Basquecs out of most of the gains they had made since the beginning of the war. In Manralia, General Buentel, newly in command, organised an army of 100000 men to try to reconquer the Province from the Basquecs. The latter had some 85000 men in the Province, but only 45000 facing the Atlanteans in the west. On March 20th, the advance started from the area of Louprut. Over the next month, the Atlanteans defeated the main Basquec army, and then moved steadily eastwards round the south of Manralia, along the highlands, following the main road called the Lairrado, and on to Nostohs. This city fell on April 16th, and Buentel now aimed to take Atlaniphis, the great fortress where the war had begun in 743. This would completely cut off the Basquec forces in Manralia from Basquecieh and all the other fronts. At the same time, a subsidiary force moved east on Noutens on the coast. However, Noutens was a hard nut to crack, containing 18000 men, and it easily held off the Atlantean attacks. At this point, Gosscalt decided he needed to be on the spot, as he did not want to lose Atlaniphis. He set about concentrating a relief force, partly from reserves on and south of the river Gestes, partly from the main armies at Helvris and Atlandravizzi. These he sent south to Ophinoutho, and followed them himself in mid May. By this time, the Atlanteans, with about 70000 men were approaching Atlaniphis from the direction of Nostohs. Gosscalt wanted to defeat this force with something better than a straightforward defence, or even counter-attack, at Atlaniphis, but he could see that his relief forces were already cut off by land from entering Manralia. He decided, therefore, on a typically brilliant flank attack from the north. He ordered the concentration of all forces in the north of the Province (except for a reduced garrison to be left in Noutens) at Dohgash, on the river Tephyens, about 100 miles NW of Atlaniphis. This amounted to about 30000 men. There were also 25000 retiring on Atlaniphis, which had a garrison of 13000, soon raised to 21000. As Buentel moved cautiously towards Atlaniphis at the end of May, Gosscalt arranged for the 40000 men he had collected at Ophinoutho to march to the mouth of the river Gayvot, opposite Dohgash and the estuary of the Tephyens. Now the remains of the great Basquec southern navy had been sheltering near Noehtens for over a year, watched by the Atlantean fleet in the Helvengio. Gosscalt left part of this in place, and borrowed the rest of it, plus other boats, to ferry his army across the water to Dohgash, entirely unsuspected by the Atlanteans. Joining this force himself, he had now concentrated 70000 men on Buentel’s flank. As the latter moved up to Atlaniphis, and began to besiege it in mid June, Gosscalt launched his army across the Tephyens and into Buentel’s flank and rear. The Third Battle of Atlaniphis was a disaster for the Atlanteans, who lost over 28000 men, and were forced to retreat back towards Nostohs. THE ADVANCE UP THE RIVER GOSAL, AND THE RETAKING OF ATLANIPHIS At about the same time as the Atlanteans were reoccupying Manralia, an army of Rabarrans, with some Atlanteans began its long advance north from Siphiya up the river Gosal. A force of 120000 Rabarrans and 65000 Atlanteans, 185000 in all, attacked a Basquec defending force of 110000 in the Siphiyans Mountains and their foothills on April 28th. After some fierce fighting, the Basquecs were forced to retreat up the Gosal. Then, for the next two months, the allies gradually compelled the Basquecs to continue to retreat through the Kharadars Mountains, and on up the river, for 300 miles, to the fortress of Kharadis. This was captured after a lengthy siege on August 12th, and then there followed a serious disagreement about which way to move next. To put this into context, we need to know that other Rabarran offensives were taking place at the same time as the advance up the Gosal. One army, of Rabarran and a few Atlantean forces, having consolidated its position in the river Katabu delta, advanced along that river eastwards towards its junction with the river Basquec. Other Rabarran units were fighting for the Basquec forts at the mouth of the river Basquec. Overall there were 200000 Rabarran men in the south of Basquecieh by August, more than in the Gosal army, facing nearly as many Basquecs. Now the Rabarrans saw this direct attack on the heartland of Basquecieh as their main strategic goal, and the threat it represented to Basquecieh was in fact evident from the reaction of Gosscalt in August. At that time, he returned to his capital, Quachach, to supervise the defence of his country against the attacks from the south. The Rabarrans were increasingly impatient with Atlantis’ prioritisation of freeing her own Empire first, which meant Manralia, Vulcanieh and Razira. To this end, she wanted to take Atlaniphis before anything else, making use of the Gosal army. Seeldu, the Rabarran Commander-in-Chief, however insisted the army turn east along the river Itheerdi to its junction with the Gairase, and then south-east up the Gedvox and into the heart of Basquecieh. Thus the Basquecs would be attacked on two fronts. Seeldu became all the more insistent as he heard during August of the counter-attacks by the Basquecs on his forces on the rivers Katabu and Basquec. Atlantis countered by saying that there were not enough men in the Gosal army to carry out this plan at present. Lengthy communications back to Cennatlantis made this dispute long and laborious, and increasingly acrimonious. Brancerix threatened to remove his forces from the Gosal army and march on Atlaniphis on his own, but knew really that the army would be too small. It was finally agreed in September to use the full army to first take Atlaniphis and destroy the Basquec army there completely, while threatening to move up the Itheerdi. Then the army would split – the Rabarrans would move up the Itheerdi, with additional reinforcements from the south, while the Atlanteans combined with the Manralian army under Buentel and marched north-east across the Gairase to attack the communications of the Basquec forces on the Gestes. The result of this compromise was an initial victory for the Atlanteans at Atlaniphis, but difficulties later, while the Rabarran advances were all stymied one after the other right into 748. So in early October, the Gosal army moved on Atlaniphis from the south, joined by Buentel from the west (where he had spent the last few months clearing out remaining Basquec garrisons in the interior, and awaiting the arrival of the Gosal army). In the climactic Fourth Battle of Atlaniphis, on October 25th, about 160000 Atlanteans and Rabarrans closed in on Atlaniphis, and the 80000 strong Basquec army there. The latter was more or less surrounded, and only 20000 men escaped. Atlaniphis, however, only fell after a full-scale storm a week later. Rabarrans and Atlanteans now went their separate ways, all the Atlanteans now coming under Buentel’s command. No more serious operations took place this year now, apart from one event. Gosscalt, accepting the temporary loss of Atlaniphis, decided that he could hamper any attempt by the Atlanteans at crossing the Gairase, by building up the Basquec garrison in Noutens. This was now the only Basquec occupied city left in Manralia apart from Dohgash. As a result, he slipped 20000 men across the water into Noutens, under cover of the Basquec fleet in the estuary. The Atlantean fleet finally tried to prevent this in November, and this led to a major fleet clash off Noutens. The Basquecs were defeated, and retired further up the estuary towards the mouth of the Gairase, but the Atlantean navy was still unwilling to follow it, due to fears about minefields and shore and floating batteries. This meant that although the Atlanteans did blockade Noutens from the sea, their efforts were repeatedly interrupted by hit-and-run Basquec naval attacks from the estuary. ATLANTIS REGAINS COMMAND OF THE MAROSSA LIRANCA Counter-offensives were also taking place in the war against Skallandieh, by both Atlantis and Gestskallandieh. The Gestskallands managed to make some progress westwards through the forests north of the Nundor Mountains, but they put their main efforts into an offensive into the Nundor Mountains themselves. They managed to take the passes south of the tallest mountain in the range, the Dorodil, moving from the source of the river Gedanleng. They made a serious effort, in so doing, to rouse the North Kelts here to take up arms against their Skalland masters, though this was hardly successful until the following year. Meanwhile, Admiral Giben was seizing control of the seas bordering Anauren and Yciel Atlantis, the necessary preparation for the amphibious landings on to Skalland territory, which were in the end planned for 748. Following its defeat in 746, the Skalland navy was unable to stand up to an Atlantean fleet, which consisted of the unified navies of Sulosos (then Atlantis) and Achosil. Throughout the year, the Atlanteans managed to land on and retake all the important islands in the Marossa Liranca, including, finally, the Suinnomiori Mandengix, just west of Alosono, in which lay the main Skalland naval base in the area. This was achieved by a fierce battle, which led to the near destruction of the Skalland naval force. The other main event at sea, on the opposite side of Yciel Atlantis, was the sortie in July by the Skalland fleet based near Arelosa, the capital of former Eliossie. This navy sailed into the Eliossia Liranca (the Bay of Eliossie), and then south through the Phonerianix Lirilix (the Phonerian straits), aiming to attack the Atlantean naval base at Achosil, or at least to take control of the seas hereabouts, and put a spoke in the Atlantean successes. The Atlanteans had most of their forces concentrated in the Marossan islands, and the small force left at Achosil was quite easily beaten at the Battle of Nundler, when it sailed up the coast of Yciel Atlantis to face the Skallands. But then the main Atlantean fleet concentrated near Phonimori island, west of Achosil, and comprehensively smashed the enemy at the Battle of Phonimori on July 29th. The remains of the Skalland fleet was harried back to Eliossien waters, and this time the Atlanteans made sure they followed the fleet up and stayed to observe it in the Eliossia Liranca. On land, meanwhile, General Elthul advanced a great distance up the low ground between the Netaka Mountains and the river Ruphaio, taking Runcairn, and moving as far as Anetako. In fact he then retired to Runcairn, because of the dangers of Skalland attacks into the flanks of this army, as he was unable to cross the river Noilafa into the main part of Marossan at all. To read the next part of this history, click on (5) 748-750 |