|

Home Page

Discovery of Atlantis

First Empire-(1) to 261

Second Empire- (1) 361 - 409 |

| 2.

The Beginning of Industrialisation, and the approach of World War,

714-743.

Despotism and

Recovery: Ruthopheax IV and Brancerix I, 714-726

A REACTIONARY TYRANT: RUTHOPHEAX IV, 714 – 721 Louron Ruthopheax IV proved to be reactionary and despotic, not just to the lower classes of the Empire, who were used to their subordinate position by now, but also to his fellow Squires. He relied for his protection on the Internal Security Armies and their commanders, and personally appointed his cronies as Officers of State, relying especially on the Imperial Minister for the Provinces and the Chief Imperial Adviser. The Chief Imperial Loyalist and the Chief Minister of the Imperial Faith were made into directors of internal security and spying, and an army of Loyalists became their strong-arm men, beating, imprisoning and torturing suspects at will. These Officers were put in direct control of the Internal Armies, taking them away from the Corps Commanders and the Governors of the Provinces. The Imperial Generalissimo retained control of the Frontier Armies, but Ruthopheax was always suspicious of his loyalty. At home, Ruthopheax tried to turn the clock back in various areas: he reintroduced the strict Class structure (715); he kept nearly all top positions in the State for Class 1s and 2s;he imposed heavy taxes on the newly burgeoning urban merchants and businessmen; and he forbid anyone under Class 3 to own land outside towns. He deliberately created an atmosphere of fear about himself, and in 716-717, he instituted a series of Show Trials in Cennatlantis and other large cities. As a result of these trials, several Army Commanders, three Officers of State, and many other gentry and people of lower Classes were tried and executed. At the same time, many of the Provincial Governors he appointed were vicious men, who acted arbitrarily and with great cruelty to many of the inhabitants of their Provinces, repeating the worst excesses of some of the earlier Governors in the time of Ruthopheax I. THE "BRADGHUS WAR" WITH UGRIEH In the first years of his reign, Ruthopheax lay low, as far as foreign affairs were concerned, and really there was no Atlantean foreign policy at all until 720. However in 718 and 720, there were two Army revolts in Dravidieh and Phonaria and Yciel Atlantis, respectively. Ruthopheax was able to crush these by inciting revolt amongst the rebels themselves, by bribing some of the leaders, and relying on his Internal Security armies especially to defeat the remaining rebels. He decided after this that his Frontier Armies needed something to keep them occupied, and deliberately incited a war with Ughrieh. This so-called Bradghus War (so named because all the fighting revolved around the town of Bradghus on Atlantis' frontier with Ughrieh) began because the Emperor complained that the Ughans were trespassing on Atlantean territory around the town and fort of Bradghus, which was itself a sort of salient in the border between Atlantis and Ughrieh. Ruthopheax crossed the border at the end of August 720, but were almost immediately forced to retreat from the strong Ughan positions in the mountains behind Bradghus (the "Kuadgh"). The Atlanteans eventually had to retire behind the Bradghus river, with a strong garrison in Bradghus itself.

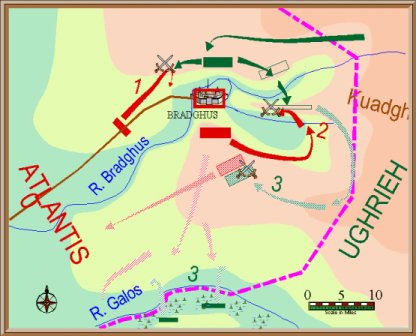

The Bradghus campaigns, 720 - 721 A second Atlantean advance north of the river Bradghus in October (1 on map above), which aimed to keep the main road through Atlantean territory into the town clear of the Ughans also failed, and both sides spent some time glaring at each other from opposite banks. Then, on November 28th, the Atlanteans began a great flank march round eastwards and over the river (2), which they hoped would force the enemy back from their position north of the town. About 72000 men set off, leaving a small force behind to fool the enemy at Bradghus. Unfortunately, due to the extremely wet and muddy weather, the march took much longer than expected, and the Army had to make the final approach on the following day. This left time for an Ughan cavalry patrol to spot the Atlanteans on their flank in the late evening. Reporting to his commander, that officer, on his own initiative, moved his troops to occupy a line of hills which, along with a small river behind the heights, to some extent protected the flank of the Ughan army. The commander initially simply moved his army to the side, behind the Bradghus, facing south-east. It was not until early morning that the Ughan commander himself fully understood the threat now posed by the Atlanteans, and moved more of his army into this good defensive position. In the Second Battle of Bradghus (November 29th) which ensued, the Atlanteans were forced to try to storm this Ughan position, before they could attempt to move further round the enemy flank. All the Atlantean attacks failed, again partly due to the boggy nature of the ground. In the end, the Atlanteans gave up, and disconsolately retreated back to their earlier positions, unimpeded by the Ughans. The Atlanteans lost 9800 men, and the Ughans 7600 out of 64000. In the early months of 721, the Ughans started to threaten to cross the river Galos, south of the Atlanteans, which would cut off their line of communications to Bradghus (3 on map).. This was a very difficult area for manoeuvering, as the river was wide and swampy, but the Atlanteans did respond to the threat. The main Ughan army now moved on a great sweep round the foothills of the Kuadgh to the south-east of the Atlantean position (3), and then attacked their army. After a hard fight, the Atlanteans were forced to retreat away from Bradghus, and the Ughans now completely surrounded the city. A regular siege now began.

River Bradghus in the Gestix Mountains at sunset

THE DOWNFALL OF RUTHOPHEAX IV, 721 At the end of 720, more plots were brewing against the Emperor, particularly amongst those Officers of State and Governors who disliked Ruthopheax and his policies, or who were under threat of arrest. Attempts were made to rope in the Imperial Generalissimo and the Frontier Armies. One Governor, of Nunchalcrieh, was betrayed by loyal Army staff, and executed. But the second Governor involved, from Vulcanieh, was more successful. At this point, a section of the armies in Dravidieh (others of which were involved in the war with Ughrieh) revolted independently. The Vulcan Armies supported their Governor as a candidate to replace Ruthopheax, while the Dravedeans preferred a man who claimed to be another of Ruthopheax II's illegitimate sons. The two sides at first fought each other, whilst loyal Armies continued to prosecute the war with Ughrieh not far away. This gave Ruthopheax time to mobilise other Frontier Armies, as well as the Internal Armies. The former were reluctant to support him, wanting first to see which way the battles would go, but the Internal Armies remained loyal to him, and moved to protect him and the capital. An initial battle against the rebel Dravedeans went Ruthopheax's way, and some of the Frontier Armies began to rediscover their loyalty to the Emperor. But now the Imperial Generalissimo came out in favour of overturning the Emperor, and set about persuading the rebels to cease fighting each other, and unite to defeat the Emperor. Ruthopheax's security forces soon managed to seize and kill the Generalissimo, but the damage done was irreparable. There now occurred a very unusual event in this period of Atlantean history - an uprising by some of the population of Cennatlantis, led by some higher officials. A stream of people, with some disaffected army units, marched out of the city to the Imperial Palaces in the countryside. At this point, Ruthopheax completely lost his nerve, and fled out of the Empire altogether, to Anauren. He cold-bloodedly left all his family behind, although a few of them did later join him in exile. Frontier Army units soon entered Cennatlantis. One of their first tasks was to put down, with great violence, the popular uprising which had ousted Ruthopheax, because nobody wanted to see the social status quo being upset in favour of the lower classes. Their two candidates for Emperor were now countered by the remains of the Imperial Government at Cennatlantis, which wanted to retain control, and they appointed a new Imperial Generalissimo, who of course supported them. In fact the Dravedean Armies' candidate was soon shown to be an impostor, while the Governor of Vulcanieh, the Vulcan Armies' candidate, was dying of wounds he had suffered in an earlier battle. The Government, with the enforced agreement of all other parties, decided to initiate a new Dynasty (Celam-Nixalen), and asked a distant cousin of Ruthopheax IV (a grandson of Ruthopheax I's sister), called Caron to become the new Emperor. He was 51, and was given the name of Brancerix I. He had originally lived in the Cennatlantis court, and had been a popular figure there up until 714. He had left and lived quietly in Vulcanieh during Ruthopheax IV's reign. He had returned to the capital in the wake of the Vulcan Army, and had been a friend of the rebel Governor of Vulcanieh. He was thus a well-known and acceptable candidate for most of the parties at Cennatlantis. BRANCERIX I AND THE BEGINNINGS OF REFORM AND PROGRESS, 721 - 725 Brancerix I proved to be a cautious reformer and liberal, who returned to the constitutional set-up of Ruthopheax III, dismissing all the placemen and cronies of Ruthopheax IV. He was a more active man than Ruthopheax III, however, in the social and political arenas. He made his first priority the ending of the war with Ughrieh, particularly as, later in 721, the city of Bradghus, long under siege, finally surrendered to the Ughans. He tried to reconvene another International Conference, but this produced no interest from any of the other Powers except Anauren. As a result, the Emperor had to make his own peace with Ughrieh, ceding Bradghus in exchange for various unimportant concessions over trade with Ughrieh. He also had to publicly accept the reunification of all the old Ughan Provinces, including the previously independent state in the north-west of the country. Meanwhile, the former Emperor Ruthopheax IV, who had fled to Anauren on his overthrow, was proving to be an acute embarrassment to that country, which desperately wanted to retain good relations with Atlantis. Anauren agreed in 723 to Atlantis' demands that that Ruthopheax should either be thrown out of Anauren or, preferably, returned to Atlantis for trial, in exchange for Atlantis releasing his wife and nearest relations to join him. Ruthopheax quickly removed himself to Skallandieh. As a result, some of his relations and cronies still in prison in Atlantis were speedily tried and executed, but the rest of his family was now told it could join him. A few did, including his wife, while others voluntarily exiled themselves to different parts of the Empire. Skallandieh was not on very good terms with Atlantis, and tried during the next few years to use Ruthopheax and his sons as a centre of conspiracy and revolt in Atlantis. Ruthopheax IV himself, who was 77 in 721, became senile over the next few years, and merely a figurehead, finally dying in 729. After this, one of his sons was hailed as the pretender Ruthopheax V. In 724 there was an attempt at an uprising in favour of Ruthopheax IV in Naokeltanieh, and a small invasion from Skallandieh of supporters of Ruthopheax. There was no real support for him in Atlantis, and the rising was easily quashed, but its leader, a son of Ruthopheax escaped back to Skallandieh. At home, Brancerix instituted a number of cautious social reforms. He quashed the edict forbidding city-dwellers to spend more than a week at a time outside their city, or country-dwellers, including peasants, to spend more than a week inside a city. This saved a tremendous amount of bureaucracy and money. After this travel between towns and countryside became more and more accepted, but cities still remained under rural local government, which, however, from now on, was often based in the suburbs of the nearest large city. Similarly, only Squires could own more than a certain amount of land, or employ more than a given number of staff, but obstacles in the way of urban dwellers moving over to becoming rural landowners were largely removed. Finally urban technological and industrial invention was well under way by now, and encouraged, and banks, invented in cities in the 680s, were now fully accepted, and used by both the urban population and rural magnates. Brancerix I died suddenly in 725, at the age of 55, leaving a wife and five children, of whom the eldest, Meison, aged 36, became Brancerix II without ado.

Industrialisation, Status Quo and the slide to Continental War:Brancerix II and III, 726 - 743 BRANCERIX II, 726 - 732 CONSERVATIVE REACTION AND THE VIEWS OF POSTERITY Brancerix II was, in most respects, very different to his father. He was essentially a conservative, who believed in maintaining the social and political set-up of the Empire as it was. He halted any further liberalisation along the lines of his father, and it was not until his son Brancerix III succeeded him in 732, that the gradual loosening of the social structure was revived. It is, incidentally, unfortunate that we lack detailed information on social and political structures throughout nearly all of the Third Empire. We do have a number of generalised comments from various sources about life in this period, but they tend to be at odds with some other historical accounts of this era. The main problem is that nearly all accounts which we possess were written not by contemporaries, but in later decades. There tend to be three ways of looking at this period. Firstly, we have purely political accounts of how the rigid social structure left by Ruthopheax I was gradually modified and liberalised, despite setbacks under Emperors like Brancerix II, by Emperors up until the Great Continental War in 743. But it is clear that, despite the claims for liberalisation, the basic structure had not changed by 749, because at that time there occurred, as we shall see, a virtual revolution, and the Fourth Empire, when it was initiated in 750, was seen as a real "democratic" Empire, in the terms of the times. Then we have the view expressed by apologists for the Fourth Empire in particular, whereby the whole Third Empire was a cruel tyranny imposed by a small elite of country Squires on all the rest of the population, especially those living in towns. Throughout this period, atrocities and cruelties were inflicted by this elite, which were as bad as anything in Atlantean history, not excluding the reign of the Tyrants in 805-828. Such writers point to the now generally accepted evidence of mass murders and deportations by Ruthopheax I in 630-670, and claim that similar events took place for the next 70 years. This is difficult to prove. Certainly cruel manhunts and strict segregation of rural and urban populations were an admitted feature of most of the Third Empire, and there is no doubt that the whole social structure was sustained by a grimly efficient police and security force. This must have involved considerable repression, at least until 720 or so, because we hear little of any rebellions or even open criticism of the regime. On the other hand, there was a continuous thread of secret, subversive literature, artistic and philosophical, at this time, which only came to light after the end of the Third Empire. After 720, there was more open criticism, and a liberalisation in literature and the arts generally, which cannot be denied. Thirdly, we must mention yet another countervailing tendency to this gloom - the opinion, increasingly prevalent in the Fifth Empire, after 828, that the Third Empire represented a sort of "Golden Age", when the Atlantean Empire was at its most peaceful, and its inhabitants were happiest. This is very obviously a gross exaggeration, except for the fortunate few at the top of the social tree, and it clearly represents a reaction against the confused period of the 830-860s, with the Tyrants in the recent past, and the South and North Empires providing a looming threat to a declining Atlantean Empire. It is notable that the ruling class in this period did not look to the Third Empire as its model - rather the Second Empire; it was the writers and artists, who really knew very little detail about the Third Empire, who idealised it as the epitome of a tranquil, well-run and politically successful state. SECRECY AND SECURITY Apart from "freezing" any further loosening of the social bonds of society, one of Brancerix's main areas of activity, as far as internal affairs were concerned, related to internal security. Hitherto the Internal Security police had been a part of the Imperial Army - the Internal Army. From 727 onwards, most internal security was placed under the control of the Minister of War, a civilian. A large Imperial Security Force was kept near Cennatlantis, however, under the Emperor's command. The growth of industry and manufacturing on a larger scale than heretofore, as well as the beginnings of small factories, had been features of a number of Atlantean towns since the beginning of the century. Brancerix was fascinated by technology, especially military innovations, and after 727, he inaugurated a number of "Secret Industrial Centres", based on towns where industrialisation was well underway. These were strictly controlled by the government, and one of Brancerix's aims here was to prevent the proliferation of industrial innovations and the widespread growth of factories. He thus sought to control innovation, which had been officially forbidden since the time of Ruthopheax I, by strict governmental oversight. A very important aspect of these Centres was in the field of military technology and innovation. Here again, all innovations had long been banned in Atlantis, Basquecieh and Ughrieh, but they fascinated the Emperor, and more importantly, he was now well aware that Basquecieh had been secretly inventing and producing new and forbidden weapons since 705. The Basquecs had resumed production, on a small scale, of breech-loading artillery, and after 712, they discovered the possibilities of rifling, which made it possible to fire much further, and far more accurately. After 715, the Basquecs also began looking at handguns of all types - muzzle and breech-loading, which had also been banned in the 660s. In 724, a military leader of genius, Gosscalt Tioch, seized control of Basquecieh, and began furiously to rearm and increase the military strength of his country. He abandoned agreements on the size of the Basquec army, brought in conscription, and hastened the production of the new, forbidden weapons, which now included explosive artillery shells, percussion cartridge bullets, and rifled muzzle-loading handguns. Brancerix II was the first to react seriously to this rearmament, largely because Gosscalt made little secret of his ambitions for Basquecieh to become a mighty power, to increase her boundaries, and humble all surrounding countries, especially Atlantis, which he hated above all. So, soon after setting up his Secret Industrial Centres, Brancerix founded a number of secret workshops and laboratories for purely military use. These were normally placed close to the Industrial Centres, and their work often overlapped, except that the military centres were wholly run by the government. These military centres worked particularly on the new gunpowder weapons, breech-loading artillery and handguns, rifled weapons, and explosive shells. As with Basquecieh, many of these had already been invented, but were then put on ice by Ruthopheax I. In other cases, Atlantis and Basquecieh spied on each other’s work. Now Atlantis was and remained some way behind Basquecieh in production, and later, in experimentation with these new weapons in wartime. Also Gosscalt introduced new military organisations and ideas, which Atlantis ignored for many years to come. On the other hand, the Secret Industrial Centres invented a much wider range of equipment, much of which was soon snapped up for military experimentation - for example, steam-power (ships, factories, land vehicles), telegraphy, mines, etc). FOREIGN POLICY The ultimate aims of Gosscalt, after he took over Basquecieh, caused considerable apprehension and alarm on Atlantis. Brancerix's secret centres were a direct result of this fright. But no real attempt was made to reorganise, increase or rearm the Atlantean Army, and after the death of the Emperor in 732, and the adoption by Gosscalt of a publicly less aggressive stance, the panic subsided, and Atlantis slipped for a while back into dangerous complacency. Indeed Rabarrieh seemed to be Atlantis' main enemy in the south, and there were some clashes at sea between them in 725-6. In 731, Atlantis actually made a secret agreement with Basquecieh, giving her a free hand to attack Rabarrieh, if she wished. This was all along, Gosscalt's aim, for he wanted to seize territory at her expense, at the same time trying out his new weapons and tactics, before later turning on his real rival, Atlantis. At the same time, he continued gradually to infiltrate into and take over the small independent states between Basquecieh and Atlantis. In 727-8, there took place a second, and more serious invasion by the Ruthopheaxans from Skallandieh, into Naokeltanieh. There was simultaneously an uprising within some military units in Naokeltanieh and Nunchalcrieh. After one or two initial defeats, these incursions were all crushed, and Ruthopheax "V" again fled. Anauren supported Atlantis in this war, and was rewarded by a small border adjustment in her favour on the Naokeltanieh frontier. THE DEATH OF BRANCERIX II, AND THE FIGHT FOR THE SUCCESSION, 732 Brancerix II became recurrently ill after 731, and died the following year. He was 43 when he died, having married three times, produced two sons and one daughter, as well as several children by various mistresses. The first son was, it was claimed somewhat retarded, certainly a dreamy, otherworldly figure, whom many thought unsuitable to become Emperor after his father's death. Brancerix knew that strictly the succession should fall to the eldest son, but Ruthopheax I had laid down that Emperors did not have to abide by this, if they had good reason not to. So, since 729, he had decided that the second son, who was only 17 in 732, but evidently a much more intelligent and practical character, would be his true heir. When he fell ill in 731, a number of courtiers, led by Brancerix's first wife and her second husband, a high-ranking Squire, had the second son poisoned. However he recovered, the plot was soon uncovered, and Brancerix had a few courtiers executed. His first wife was pardoned, her husband banished to the Southern Island (Trayanaxo), a traditional punishment in the Third Empire. In 732, Brancerix publicly declared his successor to be his second son. Opposition again expressed itself, even openly. Brancerix refused to change his mind, but then the second son was kidnapped, his mother again being involved. The two factions were now backed by two army commanders - the Imperial Security Force commander (second son) and the local Internal Force commander (first son). There was some skirmishing, but the kidnappers were seized, the second son released, and the first wife imprisoned. Brancerix still refused to have her executed, but when he died a month later, she was put to death on the new emperor's orders, and some other nobles were exiled or executed. BRANCERIX III: SOCIAL CONSERVATISM AND INDUSTRIAL ADVANCE, 732 – 749 As he was only 17 at his accession, Meison Brancerix III was supported by a Council of Regents, until he was 20. The Council, and indeed Brancerix’s court as a whole, was riven between conservatives and liberals. The former, representing the traditional, land-owning ruling classes, as well as the Internal Army, wanted to keep the social status quo, with town and country sharply separated and closely policed. The liberals, who included the urban or semi-urban gentry, as well as much of the Internal Security Force, looked to a gradual change, allowing the town-dwellers more and more access to local government, and perhaps later, to national government. There was a rather separate split, as well, between those who wanted continual innovation in industry, armaments, and even culture in general, and others who wanted all these areas included in preserving the status quo of the Empire as it had been over the past 80 years. Initially, the ultra-conservatives seemed to have the upper hand, but as Brancerix grew older, and came to assert himself more, the liberal party gained the upper hand for a while. In his twenties, Brancerix grew quite quickly into an impressive and dominating figure, but his political and social views were heavily influenced and limited by his upbringing. As a royal Squire, he could not conceive of the Squirearchy being abolished, or any real democracy reaching the lower classes. He certainly wanted to decrease authoritarian and arbitrary rule, and to improve the efficiency of the Empire by encouraging peace, trade and industry in the towns, and agriculture in the country. He went along with the party which actively encouraged industrialisation, and the invention and adoption of the new weapons of war – especially as Basquecieh was very much forcing the pace in this area. However, he disagreed with the political liberals, and after the later 730s insisted on trying to maintain at all costs the existing status quo – however rich or successful industrialists and businessmen within the towns became, they would not be allowed to help run the Empire. At the same time, paradoxically, he was very taken by the new realist tendencies in art and literature, and encouraged at least the less extreme of these writers. In 736, Brancerix II’s "Factories Limitation" Edict was partially repealed, and in 738 there followed further relaxations, as the lead established by the Basquecs in military industries became known. The factories and Industrial Areas still remained quite small-scale in the 730s, as Brancerix did not want to get involved in war and its concomitant expense. THE ARTS IN THE EARLY EIGHTH CENTURY Between 714 and 750, the most striking development in literature is the growth in importance of the novel. Although novels had been written for decades earlier, only now did it "seize the high ground" and become the most popular form of literature. It adopted the growing interest in psychology – that is, the desire to study and analyse personal relationships and the events within peoples’ minds -, which had now become a feature of philosophy and history as well. This led at first to intricate, detailed and very introspective investigations into human motives and actions on an almost abstract level. By the 730s, however, novels were becoming more "realist", that is to say, they were less psychological and more "slices of everyday life", albeit, at present, the life of well-off gentry, usually squires. After the 740s, novelists turned to middle-class town-dwellers, and later still investigated further and further down the social scale. The leading novelist of the period 735-775 was Fembeye, who initiated the move from psychological to realist novels in the 740s, and developed the novel into a far more wide-ranging and all-encompassing art-form than his predecessors. He became a great intimate of the Emperor Brancerix III. Poetry remained a formalised and "classic" art up until 750, which was rapidly losing its audience in this period. Drama was written purely for reading indoors up until about 720, as theatres had been closed by Ruthopheax II after the 680s, as he feared that they would lead to agitation against the regime. They were opened again in the 720s, and there followed a spurt of comedy, mostly written by the comic genius Sucon (711-758). Painting, like literature, was flooded by the wave of interest in realism after the 730s. Painters tried to copy real life, and their paintings became independent works of art again, not the mere decoration, which artists of the preceding decades had contented themselves with.

A retouched example of the decorative and also realistic nature art of the mid Third Empire Music emerged defiantly from its chamber music shell in this era. After 720, bigger-scale instrumental and, later, orchestral works were written, leading to the growth of genuinely symphonic works. There was now a renewed interest in melody, less complex rhythms, and a more Romantic style harmony developed after the 750s. THE GROWING THREAT OF BASQUECIEH In the year of Brancerix’s accession, Basquecieh, under the leadership of the brilliant general Gosscalt, invaded Rabarrieh. At first Brancerix tacitly sided with the Basquecs, as Atlantis had long been worried by the growth of Rabarrieh on its southern flank, and by the way in which it, along with the Far Southern Empire, could effectively block and control the straits between the Great Continent and the continent to the south. Gosscalt used this war to try out his new weapons, at the same time as eliminating Rabarrieh, as he hoped, as a serious threat on his flank when he came to the great trial of strength with the Atlantean Empire. He acted appeasingly towards Atlantis throughout the period of this war against Rabarrieh, carefully hiding his use of new weapons by using them only in small numbers in critical battles. His scheming was very successful, and Brancerix and his cabinet signally failed to take alarm at Gosscalt’s aggression. Nevertheless, as the Basquecs gradually conquered the whole of the north-east of Rabarrieh’s territory, that is, all land between Basquecieh’s borders and the river Gosal to the west, Brancerix did become concerned, and sought to mediate peace. Gosscalt did make peace, finally, in 737, but only after he had obtained nearly all the territory he wanted, badly demoralised the Rabarrans, forcing the overthrow of Athulzu Alakultire, the king of Rabarrieh, and successfully carried out the weapons trials he needed. At the same time as all this, Gosscalt was gradually taking over the neutral and demilitarized minor states to the east of Razira, and the south-east of Vulcanieh. By 742, Basquec forces were in Laccues, north of the river Baccuel, and had reached the borders of Vulcanieh. In 736, Gosscalt made a secret alliance with Emperor Yrultak of the Ughans, and Ughrieh agreed to support Basquecieh in a war against Atlantis. Military experts and weapons were sent to Ughrieh to help her improve her military capabilities, and supply her with the (almost) latest technologies. Now a number of Atlantean military chiefs took alarm, and warned the Emperor that a hostile alliance against Atlantis was rapidly being built up. But Brancerix made little attempt to prepare the Empire for war, and continued on in a dangerous complacency. THE GREAT ALLIANCES TAKE SHAPE Nevertheless, other alliances were beginning to be formed, alliances which would involve nearly every state on the Great Continent in war, once any one of them was attacked by another. In 734, Quendelie, (the Western Empire) was granted the right by Atlantis to have trading posts in the Phonerian Isles, as well as Phoneria (already since 706). Relations between Atlantis and the Quendelie grew still closer over the next 10 years, to the extent that small Quendelien garrisons were also allowed in some of these ports. However, Quendelie was the one major state which was not to be involved in the forthcoming War – it stayed resolutely neutral. This accord did, just the same, alarm Anauren, with which Atlantis had been on close terms for decades, and it began to build up its navy, making use of the latest ironclad designs and steam-engines, which Atlantis had initiated. Skallandieh and Atlantis then also increased their naval production, and something of a naval arms race set in between these three Powers. In 740, Razira, a demilitarized, independent state, suddenly declared itself an ally of the Basquecs, in defiance of the historical convention that it should always stay neutral, and favour Atlantis in general. Basquec troops poured into its territory, supposedly by invitation. War with Atlantis looked inevitable, and Gosscalt had planned all this, and believed Brancerix would back down first. He was right. Brancerix agreed to Razira’s new alliance, as long as Basquecieh removed its troops, and Razira City itself became an Atlantean possession (with a nominal garrison of 5000 men). Gosscalt knew it would be completely indefensible in war, and he had anyway obtained easy transit for his armies through Raziran territory, supported by the Raziran Army. Between 740 and 743, Basquec armies moved into all the states bordering Vulcanieh and Manralia, and trickled into Razira itself (apart from the capital), despite the agreement with Atlantis. A whole Army also moved into S.Ughrieh, as part of Gosscalt’s grand strategy against Atlantis. Gosscalt had also for some years been wooing Skallandieh, in order to threaten Atlantis on its northern flank. It supplied it with weapons and military advice throughout the 730s, and encouraged it to attack Atlantis, once Basquecieh was at war with her. This led to a secret alliance in 738. In fact Skallandieh wanted above all to have greater access to the sea, and was more than a little scared of Atlantis itself. So Gosscalt cunningly persuaded it to attack Anauren and the states to the north (formerly in Eliossien territory), seize their assets. He claimed that Atlantis, tied up by the fighting against Basquecieh and Ughrieh might very well not come to Anauren’s aid, and then Skallandieh could pick its moment to attack Atlantis later. He knew these invasions would tie up Atlantis diplomatically, and would in any case force her to come to Anauren’s support – but later rather than sooner – probably too late -, because of the recent cooling-off in the relations between Anauren and Atlantis. Gestskallandieh (the NE Empire) had been at loggerheads with its N.W. neighbour for years, and the way was now open, once war had begun, for Atlantis to bring her into the Atlantean camp. Thoroughly alarmed at last, after 740, Brancerix started serious mobilization of his armies, and made an offensive-defensive alliance with Rabarrieh in 741. This was followed directly by the start of the "Great Continental War" in 743, when Gosscalt attacked Atlantis, and gradually all the other allied countries joined in the conflict. This war is described in detail in the next chapter of this book, and we shall at this point simply round off the reign and life of Brancerix.

THE OVERTHROW OF BRANCERIX III AND THE FINAL YEARS OF HIS LIFE Brancerix was in character a most unmilitary man, who disliked war, and wanted only to preserve peace for the good of the Atlantean Empire. Nevertheless, when war, in the shape of the Great Continental War, was thrust upon him, he rose magnificently to the challenge. Despite terrible defeats in the first two or three years of the war, as well as the opposition of the military genius of Gosscalt, Brancerix managed to co-operate with three nations (Gestskallandieh, Rabarrieh and Atlantis), against the coalition of three states which had declared war on him (Basquecieh, Ughrieh and Skallandieh) and lead Atlantis to virtual victory by 749. He made no attempt to take part in military operations himself, but he acted as Commander-in Chief, hiring and firing generals, suggesting strategy, and making sure the production of the new rifles and breech-loading cannon went ahead at top speed. However, the stress and strain of the war took its toll both on Brancerix himself, and more seriously on the whole social structure of the Third Empire. As Atlantis and its partners finally approached victory over their enemies in 749, opposition to the Emperor and the Squirearchy at home reached its climax. Brancerix was ousted by a military coup, and retired to his estates in south Nunchalcrieh, as civil war and chaos threatened to overwhelm the whole Empire, just as it was gaining victory on the battlefield. During the tumults of the following two years, his estates were overrun and some of his properties set on fire. He was given a small military guard, which indeed had to defend him on one occasion. He had married in 739, and by 749 had five children, all of whom were now together on this estate with his wife and himself. Finally, in 751, his estates were confiscated, and he and his family fled to the western coast, there to take ship and retire to Th. Thiss., where a small property had been kept for him. The family remained there for a short while under house arrest. Against his personal wishes, the new Emperor, Sualofo Thildoyon was forced to bow to popular demand and exile the former imperial family to Penedrin, the "Southern Island", way out in the south seas. Brancerix lived there in the small town of Vivost for over 30 years, returning to the mainland only twice on brief, permitted visits, until his death in 787, at the age of 72. To read about the Great Continental War, click on The Continental War- (1) 743 |