|

Home Page

Discovery of Atlantis

First Empire-(1) to 261

Second Empire- (1) 361 - 409 |

|

A COSMOPOLITAN AND LIBERAL PRINCE Lasso was adopted as Emperor-to-be by his father, Iustos, in 404, following the decision made much earlier in the reign that the imperial succession should devolve by adoption of the best person, rather than automatically by hereditary succession as had happened hitherto. In practice this had little effect as the line of emperors remained within the same family. Lasso had been brought up in an enlightened fashion by his father, and was certainly the most intelligent and capable of his siblings, as well as being fortuitously the eldest male heir. When 24 years old, he married Suayosa, the beautiful and intelligent daughter, of a noble Helvran, who was an Imperial Controller at this time. This was a happy marriage to begin with, and it certainly helped to kindle Lasso's cosmopolitanism and interest in all parts of the empire. Throughout his reign, Lasso travelled far and wide, and visited every Atlantean province at least once, as well as going abroad on sea journeys, and making state visits to Eliossie, Razira, Vulcania and Ugr´eh (the latter only in the course of a military campaign!) He deliberately encouraged non-Atlanteans to reach high posts in government, and granted full citizenship to the Provinces of Manralia's southern border, Borchalcr´eh and Yallandix Thissandix, and initial citizenship to Meistay´eh, Naokeltan´eh and Dravid´eh. Equally he did much to encourage, indeed, initially, to force, uniformity of practice in law, education, language and other social practices throughout all the Provinces. One of his most important innovations was the abolition in 422 of the old Class system (though it has to be said this never really died, and came back to life later in the Second Empire). Lasso's cast of mind was very similar to his father, and he followed his generally liberal ideals in matters of government and social policy. However he was also much more interested than Iustos both in creating a successful cosmopolitan empire, and imposing a centralised and uniform method of government on all the Provimces. He was also intensely interested in warfare, and the military art, and in the first part of his reign, was determined to bring, by conquest, more peoples into the Empire of Atlantis THE HELVRAN REVOLT - THE IMPERIAL FAMILY AT WAR WITH ITSELF Lasso, despite his interest in the different races that made up his Empire, believed that the administration of such a vast body of peoples was only possible if they all used the same principles of law and education, and all spoke the same language, Atlantean, at least for all public purposes. In these matters, he reversed some of his fatherĺs liberal ideas, and imposed these practices quite harshly at first: this caused considerable resentment, especially amongst the Helvrans, Jutes and some of the Kelts. In the end this led to the Great Revolt of the Helvrans in 420-1. In some ways this was a reaction to the liberalisation granted by Iustos, which reversed a century of linguistic and political pressure against old Helvran uses, and which now seemed again to be put under threat by the new Emperor. The first outbreaks of revolt in the Helvran areas were severely dealt with by the Atlantean army, with the tacit support of Lasso. But then, his wife, Suayosa, of Helvran origin herself, personally objected to this treatment of her fellow country folk, and symbolically changed her name to its (original) Helvran form, Slilin. Her eldest son also ran off and joined the rebels. Lasso at first would not change his views, claiming that his son had been kidnapped by the rebels. The climax to all this came in two weeks in 421, when Lasso, touring supposedly pacified areas of Helvr´eh was nearly assassinated, his wife then suddenly vanished, and his rebel son was killed in action fighting against the Atlantean army. Stunned, Atlaniphon now turned to compromise, and the Revolt gradually ended. Helvr´eh was to retain its present rights, as granted by Iustos, which nevertheless dwindled away over the following decades - although the Helvran language, still taught officially in schools for the next century, survived and was even to be used in duplicate with Atlantean in official documents until the middle of the next century. Atlaniphon's wife returned to him some months later from her hideout, but their relationship was never the same again, and they later lived apart. Suayosa died in 439, heartbroken also by the scandalous behaviour of one of their granddaughters, and Atlaniphon never remarried. CLASSICAL ART REACHES ITS ZENITH The reigns of the three Atlaniphon Emperors saw the rise and supremacy of classical art, including literature and architecture. The great literary names were these : Rasiphel (339-398), who is chiefly known as a writer of "classical" poetic dramas. They used a very limited number of metres and a small, elevated vocabulary, and were highly prized by Atlaniphon I as "Imperial Drama". Rasiphel's successor, during the reign of Atlaniphon II, was Normell´el (400-461). Like Rasiphel, he saw himself as a poet first and a dramatist second. He developed the purely dramatic elements of his plays, and increasingly collaborated with musicians for accompanying music. The later plays were also set in specific landscapes, and should be played in particular locations. Finally we must mention the great poet Huatt´ens (361-447), who was the poet of the classical First Empire "par excellence". In all cases, the classical canon prescribed the avoidance of writing in the first person, instead making use of the third. This was the case even in spoken drama. Lasso also had two monumental statues of Atlaniphon I sculpted at Miolrel and Atlantis (not far from the much earlier monument to the Atlantean victory over the Helvrans). THE EMPIRE REACHES ITS FULL EXTENT - THE SECOND UGHAN WAR ("BUOUYE CREHEI ANTE UGHANIX"), AND THE BATTLE OF YRULLIA The Empire continued to grow during the 420s and 430s, with Lasso himself planning and leading some campaigns. Between 416-419 south Nunchalcr´eh was conquered and made a Province in 421. In the 420s there was fighting with the N. Kelts, and further lands conquered (The Province of Geskeltan´eh was formed in 431.) Lasso was keen to protect the frontiers of his huge Empire, and started to build a series of strongholds around the borders, especially along the river Gestes in the east - these included Dravipand and Atlanipand on the Gestes, and Keltanipand in the north. ("Pand" is simply the Atlantean for "fortress".) However, the revolt of the Helvrans in 420-1 turned the Emperorĺs mind increasingly to equality and liberalism for the peoples of the Empire, with toleration for local customs and languages. He avoided wars during most of the 430s, but then the increasing number of raids by the Ughans into Atlantean territory forced him to try to break this powerful neighbour after 439. This war, which he led personally rekindled his fascination for warfare, and his success in it induced him to risk the great Invasion of the East after 444. This proved to be a step too far even for the undoubted military abilities of the Emperor, and after it was over, he declared he would give up fighting and imperialism for all time. The Second Ughan War took place in 439-443, and the Atlanteans, after inconclusive fighting in the Gestix mountains, marched north and north-east through Nunchalcrieh and the Diefillen, round the northern end of the Mountains. This march of over 200 miles surprised the Ughans, led by Tjaidli, who were beaten overwhelmingly in 441 in a battle across the Gestes. In 442, the Atlanteans moved south and faced the Ughans again at Yrullia. The Battle of Yrullia, 442, is a typical example of Classical Atlantean battlecraft. Atlaniphon led an army of nine Pueggisix, or 86000 men, 9000 of them cavalry, plus artillery and mounted infantry. The Ughans had 95000, mostly swordsmen , with some units of light bowmen, and 20000 cavalry. The Ughans formed up in two lines with their left flank on a river, and their centre and right on separate hills. Atlaniphon planned to seize this hill, which was held largely by Ughan bowmen, and then work against the Ughan flank, seeing how things developed. In fact the Ughans moved first, sending cavalry and some infantry over the river on the left against the Atlantean flank. The Emperor counter-attacked, but his forces over here were forced to retreat again later. But already he was moving cavalry and two Armies against the hill on his left, which he had already sent mounted infantry on ahead to seize. After a short struggle, the hill was taken, but other Ughan forces counter-attacked it. Next, units on the Ughan left advanced quickly against the Atlantean right wing. This was successful at first, but Atlaniphon brought up his reserves, including cavalry, and counter-attacked, forcing the Ughans to flee. The Atlanteans now moved forwards with the centre, bombarding the Ughans on the hill there in advance. They were helped by their right wing, chasing the fleeing Ughans. A tough struggle for the hill ensued, but potential Ughan reinforcements were distracted by the Atlantean extreme left-wing, which, having secured the hills there, was now drawing off the Ughan reserves. Finally the two Armies to the left of the Atlantean centre also advanced, forced back their opponents, and attacked the central hill from the flank. This finally routed the Ughans, and Atlaniphon triumphed at the cost of 6000 men. The Ughans lost 18000 and 10000 prisoners. As Atlantean forces now moved towards the Ughan capital, Gargros, Tjaidli was quick to seek terms. Lasso took over the whole of the Diefillen area for the Empire (previously an independent area partly under Ughan suzerainty), and also secured a large chunk of Ughan territory to the east across the Gestes, as far as the Cugh (river) Teceg. This included an important pass through the Gestix Mountains, the Teceg Buoumu, from the river at Fembepand. At the far end of the pass, Lasso had a great new fortress called Iustupand built, named after his father. At the same time, Vulcanieh, which had played a minor but important part in the war, threatening the southern confederation of Ughan states, with its capital at Psjasegargros, and thus preventing its rulers from supporting the northern kingdom. In 442, the Vulcans actually invaded their northern neighbour, and took a slice of territory south of Psjasegargros after 444.

Evening over the Gestes river

THE FIRST INVASION OF THE EAST, 444 - 446 No sooner had he finished with the war against Ughrieh than Lasso, his interest in practical warfare well and truly kindled, decided to start a campaign which would really make his name famous in history. Atlantis had long traded with the distant countries and cities of the far east, either by sea or overland, in both cases a distance of many hundreds of miles. This trade overland to the south-east via Vulcanieh or Razira was at the mercy of both the nations or peoples lying along the route and the trading cities beyond, which mostly lay on the sea at that point. Atlantis had little definite idea of the political set-up of these towns or the countries beyond, from which the items traded actually came. It was believed, correctly, that there was a large empire involved. Lasso had been turning his options over in his mind for a couple of years before 442. Now, as so often before, middlemen along this trade-route were charging ruinously high prices for importing and exporting goods: furthermore, two of the little kingdoms on the other side of Vulcanieh had become completely hostile to such trade. The Emperor decided to move an army of 100000 men down to the river Baccuel, and simply march east, quashing hostile forces en route, arrive at the trading-ports, capture them, and then trade directly with the mysterious empire to the east, fighting it too, if necessary. A large navy would sail there too, meeting the land forces and helping to blockade the towns. Vulcanieh had no choice but to allow the Emperor access, as well as to provide him with allied troops to help hold the long lines of communication. The army, led by the Emperor, set off from Laccuel in May 444. It marched down the river, skirting the north of the area of the Polder Folk, and entered mountainous territory. With some difficulty, the Atlanteans forced their way through, defeating hostile peoples, and leaving garrisons behind and strategic intervals. Further on, the mountains gave way to steppe, and crossing these caused Lasso considerable wastage of troops. He finally came to the far side, and was faced with four large city-states, which had been expecting him, and had prepared defences. Lasso made contact with the great Empire of the East, Losang, while besieging two of these, and tried to reach a moderately amicable agreement in which the Losang remained neutral, to the future benefit of her relations with Atlantis. However, he failed. Losang did not want this western Power intervening so close to home, and declared war on the Lasso. The next year saw part of the army besieging and storming two of the ports, Amtas and Ganaptas, while the navy tried to blockade them by sea, But there was a nasty surprise when a large Losang navy appeared and defeated the Atlanteans. Thereafter, the navy was not really able to stand up to the larger and stronger enemy ships, and could play little part in the war. On land, the sieges went slowly, and Lasso had to ward off at least one attack by Losang. By the autumn of 44 he held Amtas and Ganaptas, had the third city, Mauntan, under tight siege, but had done little against the fourth, Sarapas, as it was constantly being succoured by Losang troops. So now Lasso marched with 50000 men (he had received only a few reinforcements) into the territory of the Empire of Losang. There were, it seems, two major battles: the first led to a severe defeat of the enemy. Lasso pursued eastwards, deep into enemy territory. The army of Losang stood at bay in a very strong defensive position, and all attacks against it by the Atlanteans failed. With casualties of over 16000 men, Lasso had to admit defeat and retired back to his siege. The port of Mauntan finally fell early in 446. THE TERRIBLE RETREAT Lasso now realised that he had won as much glory as he ever would. Tribes along his long line of communication were rebelling; his navy could not face the enemy at sea, and he could only remain on the defensive against it on land. Furthermore, he had little chance of obtaining reinforcements for an army which now amounted to only 55000 men. He needed to retain most of his troops to protect his Empire, and in any case transport eastwards by sea was risky, and by land involved entanglement with the rebellious tribesmen. Lasso now betook himself home with a guard of 15000 men, most of which he dropped off to strengthen garrisons en route. He also persuaded the Vulcans to contribute 14000 men to protect this route. In the east, he left behind 20000 men to garrison the three captured towns, while 20000 guarded them against Losang. For a while, the Atlanteans maintained their positions, and were able to dominate the trade-route. But this war, however successful, sickened the Emperor by the huge casualty list which had resulted from it. In 447 he personally abjured war and declared the Atlantean Empire "complete for all time". He withdrew some 11000 more troops from the east, but maintained all the rest there. Even before his death, the situation deteriorated, as a huge Empire army arrived on the scene and besieged one Atlantean-held town. The new Emperor, Carel, who assumed power in 448, was a pacific, arts-loving man, and had no interest in his predecessor's mad expedition to the east. But neither would he act decisively to withdraw the troops. As a result, things quickly went from bad to worse. Revolts along the line of communication led to nearly all the garrisons being besieged. At the same time, in the east, Mauntan was stormed by Losang and allied troops, and most of the garrison massacred when the survivors finally surrendered. Ganaptas was now besieged. Later in 449, the Vulcans declared their neutrality, and abandoned all their garrison positions. Finally, almost too late, Carel gave orders for his troops to leave the towns, and fight their way back westwards, bringing along all the garrisons en route as they retired. The navy made one attempt to pick up troops by sea, but was beaten back by the enemy. The retreat of the Atlanteans overland via desert and mountain to Vulcanieh and on to the Gestes was an epic, though disastrous, marathon of courage and endurance. Firstly the march took place in ever worsening weather from November 449 to March 450. The troops were repeatedly attacked from the rear by Losang and other forces right into the steppes. Then, and especially in the mountains, they were attacked by the local warbands. These had already taken and killed a number of the garrisons en route, as well as the supplies stored there. The retreating troops marched from waypoint to waypoint, often having to storm when they were in enemy hands, sheltering and recovering in each of them, and then continuing their march. Of 30000 troops who began the march, and 13000 holding the forts en route, only 8000 straggled, exhausted, into Vulcanipand in March of 450. Thus an army of over 100000 which had set off eastwards in such high hopes in 444, was reduced in the end to just these 8000 barely able-bodied soldiers. During the campaign, perhaps another 18000 wounded had returned home and survived their injuries, at least to some extent. All the rest were dead, or prisoners - and virtually none of the latter ever returned. "Puainetto pueggisayu aithe puainetto cer´ehayu". "The strength of the army is the strength of the empire." Atlaniphon II, 439.

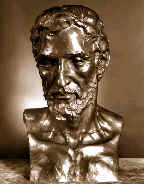

The statue of Atlaniphon II set up THE END OF THE REIGN Following the end of the War, Lasso went into semi-retirement, and soon became quite ill. He turned his thoughts to the succession. He had no son, and although he did have two daughters, he could not envisage leaving the empire to a female ruler. Looking beyond his own children , he sought a pacific, conciliatory, cultured man, who could be a capable administrator, and initially considered one or other of his Controllers. But in 445 he finally decided upon one of his elder brother's children, Carel, then aged 26, who was living quietly on his estate in Chalcr´eh, unmarried. He held a post there in charge of the arts and games, and was himself the centre of an artistic circle. He met many of Lasso's criteria, and he knew him personally. His administrative abilities were fairly unknown, but Lasso intended to pass on to him the best of his Controllers. Thereafter Lasso's powers gradually declined, and he died after a long illness in 448.

The Patron of the Arts : Carel Atlaniphon III, 448-478.

A portrait of Atlaniphon III in the late 470s AN ART-LOVING RULER Carel proved to be the non-imperialistic, retiring, Atlantis-loving Emperor that Lasso had hoped for, although he ultimately became more retiring and wilful than he at first seemed. He never married, and was in fact homosexual, finding his greatest fulfillment in the arts and the company of artists. He indulged in and encouraged all the arts, including the laying out of great landscaped gardens, and the organising or sponsoring of settings for the new "Total Works of Art". He started the trend for living away from both towns and farms, on country estates where the well-off could indulge in fantasies of an ideal and leisurely life. His circle, very much an elite, spearheaded the gradual turn in the arts, and indeed the Atlanteans' whole outlook on life, from Classicism to Romanticism, and his great protÚgÚ was Gildasso, the Chalcran composer and first great exponent of Total Works of Art. The Total Work of Art represented the fusion of music, drama and landscape into one art-form. Gildasso (431-485) wrote plays entirely in prose, and in a new, much more emotional manner than his predecessors. He concentrated on "historical" subjects (pre-361), and claimed that drama should above all be natural and truthful. He encouraged collaboration with all the other arts, and in fact coined the phrase "Total Work of Art" in 455. The Emperor was fascinated by his work, and willingly created whole landscapes to be the setting for his dramas. Carel also found an outlet for his artistic talents in architecture and landscape. Most notable was the great new Imperial Palace he built some miles to the north-east of Atlantis city. This new Palace was really quite unnecessary and an extravagant waste of money, besides separating the Imperial Court from ordinary people within Atlantis itself. But the design and decoration of the buildings fascinated the Carel, and the results were a genuine collaboration between architects and Emperor. A GOLDEN AGE This period in Atlantean history was in later times looked back on as perhaps the most settled and happiest in her history. While Atlaniphon I was granted the accolade of the greatest of the Emperors of Atlantis, presiding over the most glorious and militarily successful period of the Empire, Atlaniphon III reigned during the most peaceful, most settled and happiest era for the inhabitants, a genuine "Golden Age". Carel hated warfare and in his time there was no deliberate external fighting. The only war of any importance, into which Carel had to be forced, was with the king of the Vulcans, Yrulwas, against Razira in 464-466. This was caused by the action of Atlantean traders in Razira secretly supporting revolts against Raziran over lordship. In 464, following a massacre of these traders by the exasperated Razirans, Atlantis and the Vulcans declared war. Razira was ruled by a matriarchal monarchy, and the Queen at this time was Zovahh. The decisive battle of the war was the Battle of Razira in 465. THE BATTLE OF RAZIRA, 465 The Atlanteans, led by Carel Atlaniphon, had an army of seven Pueggisix, about 66000 men, plus a Local Army of 3000. As well as 50000 infantry, therefore, there was about 6500 light cavalry, 2000 medium cavalry and some 5000 mounted infantry. The Razirans, led by Queen Zovahh, were about 65000 strong, including 35000 swordsmen, including the Royal Band. There were only 5000 medium bowmen, as well as 5000 light bowmen, 9000 medium cavalry and 11000 light cavalry. The battle, like most fights of this era, consisted of a series of attacks and manoeuvres by different units of the two armies against each other. The Raziransĺ moves were ill-co-ordinated and fairly random, resembling those of the Atlanteans during the latter part of the First Empire. The Atlanteans of this period, however, attacked and reacted according to a carefully thought out tactical plan, and that is why they nearly always won their battles. (The map shows the order of the attacks).

Firstly of all, the Raziran medium cavalry on their left flank charged and ultimately put to flight the weaker Atlantean cavalry (map 1).. However, the nearest Army prevented further Raziran incursions here. (2). Meanwhile, on their left, according to plan, the Atlantean mounted infantry and cavalry seized a hill on the right of the Raziran position, which was only lightly held by light cavalry. (2). A Yalland Army followed up and took possession of the area. Next, the two frontline Armies on the Atlantean left, Yallands 1 and 2, moved against their opponents. (3).They were held off and the Raziran forces to their left attacked the Atlanteans in flank. (4). The next Atlantean Armies in line, Meistayieh 1 and 2, now advanced and hit the exposed flank of these Razirans, in turn. (5). The battle was, however, still undecided in the centre, so the Raziran Royal Band, led by the Queen herself, now threw itself into the central fray, while some parts of it moved to the right to protect the rest from the growing number of attacks from the Atlantean forces on the left-hand hill. (6). In this crisis, the remaining Atlantean Army, Manralia 1, hastened to the centre and forced back the Royal Band. (7). This was now also attacked in flank from the Atlantean cavalry and infantry on the hill, and the whole Raziran position crumbled. The Queen and the remains of her army fled, leaving behind 15000 casualties. The Atlanteans lost 6300. Soon after, the Razirans admitted defeat, the Queen fled and Razira was made into a dependent state - with a pro-Atlantean princess to rule her.

Carel had no immediate family, and decided in 468 to adopt as the next Emperor his great friend Thildo Suayofo, an inward-looking artist. Carel's advisors warned him several times that Thildo was not suited to the imperial role, as he was too moody, self-centred and misanthropic. Carel refused to change his mind, and even, finally, banished the last person who criticised his choice. He died in 478, thrown from his horse whilst galloping round a new open-air theatre. "Atlan folg´ens fulgienethe tuaincuyehe tontan toumanan puouth´enaxan." "The Atlantean sun shines brightly on the whole civilized world". ( Gildasso, 468)

To read the next part of this history, click on (3) 478-511 |

In government, Carel

saw himself merely as an arbiter of last resort, and increasingly

abstracted himself from meetings and actual decision-making after the

460s. He could nevertheless assert himself from time to time, and had a

wilful, even cruel streak. On several occasions he refused clemency to

friends or colleagues whom rumour accused of breaking Atlantean laws

(fraud, murder, treason). Famously in 471, and despite pleas from

others, he insisted on the death-penalty for one of his nephews, the son

of a Controller, who had organised a secret wargame involving real

fighting.

In government, Carel

saw himself merely as an arbiter of last resort, and increasingly

abstracted himself from meetings and actual decision-making after the

460s. He could nevertheless assert himself from time to time, and had a

wilful, even cruel streak. On several occasions he refused clemency to

friends or colleagues whom rumour accused of breaking Atlantean laws

(fraud, murder, treason). Famously in 471, and despite pleas from

others, he insisted on the death-penalty for one of his nephews, the son

of a Controller, who had organised a secret wargame involving real

fighting.